“We’re bankrupting a lot of hospitals by forcing these hospitals to provide care for people who don’t have the legal right to be in our country.”

Sen. JD Vance (R-Ohio) during a Sept. 17 rally

During a recent presidential campaign rally in Wisconsin, Sen. JD Vance (R-Ohio) was asked how a Trump administration would protect rural health care access in the face of hospital closures, such as two this year in Eau Claire and Chippewa Falls.

In response, he turned to immigration.

“Now, you might not think that rural health care access is an immigration issue,” said Vance, former President Donald Trump’s running mate. “I guarantee it is an immigration issue, because we’re bankrupting a lot of hospitals by forcing these hospitals to provide care for people who don’t have the legal right to be in our country.”

More than 150 rural hospitals have closed or eliminated inpatient services since 2010, researchers at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill reported. Losing a hospital can resonate throughout a community — reducing access to timely care and disrupting the local economy.

The federal government has made efforts to keep the far-flung facilities afloat, but it’s not been an easy problem to solve.

What Is Plaguing Rural Hospitals?

Experts said Vance’s statement implies that immigrants who are in the country illegally strain the resources of these hospitals, which often operate on thin margins, by taking time and energy away from other patients without paying their bills.

We contacted both Vance and Trump campaign staff members for additional information. They did not respond.

Experts on hospital financing and industry representatives generally disagreed with Vance’s assertion, noting that many other factors figure in closures.

“When we speak with our rural hospital members, that is not what we hear,” said Shannon Wu, director of payment policy at the American Hospital Association, a trade group of more than 5,000 hospitals around the country.

Brock Slabach, chief operating officer of the National Rural Health Association, said border state hospitals face challenges treating immigrants who are in the country illegally. “But I’ve never, in my discussions, had anyone link it directly to a hospital closure,” he said.

The specific situations that lead a rural hospital to close its doors are unique to each facility, researchers said, but many face some of the same stressors.

Rural hospitals tend to have low patient volumes, which presents its own set of problems. They’re frequently located in small communities, and some residents may choose to travel to hospitals in bigger cities where they can get more complex care, what researchers call “hospital bypass.”

That small number of patients can cause financial losses at small rural hospitals, said Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a national health care payment and delivery systems policy center.

Hospitals have fixed costs, such as for running emergency departments, and need to have a high enough patient volume to cover them, he said.

“If a patient comes into the ED and doesn’t have insurance or can’t pay, it doesn’t really increase the cost to the hospital very much at all because the physician is already there,” he said, using an abbreviation for emergency department.

Rural hospitals treat a higher share of patients covered by Medicare and Medicaid compared with urban hospitals, according to the American Medical Association. The public insurance programs for older and low-income Americans generally pay providers less than private insurers do.

Nevertheless, Medicare is “one of the better payers” for small rural hospitals, Miller said. That’s partly because facilities with a special “critical access hospital” designation get paid more by Medicare — and, in some states, Medicaid.

Hospital industry officials and some experts say Medicare Advantage plans’ rising popularity has also hurt rural hospitals’ bottom lines because the private insurance companies that offer the plans tend to be less reliable payers than traditional Medicare.

For starters, the negotiated rates paid by Advantage plans can be lower, which is especially noticeable for those critical access facilities. Advantage plans also introduce extra levels of expensive, staff-intensive administrative burdens to ensure payment.

“They’ll deny the claim or say the patient really didn’t need that service through prior authorization, and so the hospitals don’t get paid for the service from someone who has insurance,” Miller said.

The insurance industry trade group AHIP pushed back on the assertion that Medicare Advantage plans harm rural hospitals, citing a federally supported study saying the plans actually increase rural hospital financial stability.

But the study did not compare actual payments between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare plans and looked at only 14 states.

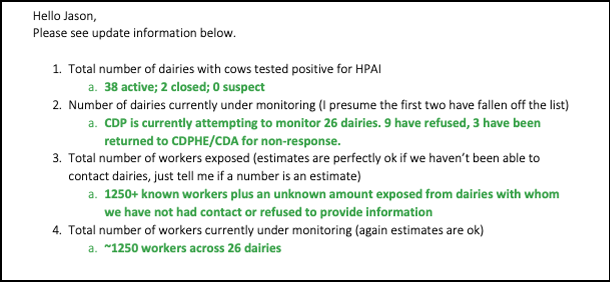

People lacking legal immigration status generally cannot obtain Medicaid or Medicare coverage. But a provision within Medicaid law does allow some immigrants in the country illegally to temporarily obtain coverage, said Hayden Dublois, data and analytics director for the think tank Foundation for Government Accountability.

Medicaid, which pays less than Medicare and private insurance, “is not exactly a financial boon for hospitals,” and this could be some of what Vance is referring to, Dublois said.

In data from a few states, Dublois found a rise in people enrolling in Medicaid without being able to verify their immigration status. But his research hasn’t looked specifically at how this population might affect rural hospitals’ financial viability.

Some states have acted in recent years to expand health coverage to people in the country illegally — offering insurance to more than 1 million low-income immigrants.

One of those states, California, has had nine hospitals close or end in-patient services since 2005.

People may be able to pay out-of-pocket for care, researchers said, or may have access to private insurance through an employer.

Covering the costs for the uninsured is only one financial stressor rural hospitals face, said George Pink, deputy director of the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program.

“Is that going to be enough to drive a hospital into bankruptcy? Probably not,” he said.

A financial decline can take years, Pink said. As losses mount, hospitals can be forced to sell property or other assets, draw down any financial reserves, and max out their credit.

“This is not an overnight phenomenon,” he said.

Our Ruling

Vance said providing care for immigrants without legal status was “bankrupting” rural hospitals and forcing them to close.

Although that population is more likely to be uninsured, living in the country illegally does not mean people lack the ability to pay for health care — especially if they live in states that offer them insurance coverage.

Research shows many factors contribute to rural hospital closures — not solely financial losses from providing care for those without insurance, whether those people are migrants in the country illegally or U.S. citizens.

We rate Vance’s statement False.

Our sources:

PBS NewsHour, “WATCH LIVE: Vance Addresses Campaign Rally in Eau Claire, WI,” Sept. 17, 2024.

HSHS Hospital Sisters Health System, “HSHS Sacred Heart Hospital and HSHS St. Joseph’s Hospital Closure Information,” accessed Sept. 26, 2024.

Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, “Rural Hospital Closures,” accessed Sept. 27, 2024.

GAO, “Rural Hospital Closures: Affected Residents Had Reduced Access to Health Care Services,” Dec. 22, 2020.

The Journal of Rural Health, “The Impact of Rural General Hospital Closures on Communities — A Systematic Review of the Literature,” Nov. 20, 2023.

Rural Health Information Hub, “Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs),” accessed Sept. 30, 2024.

KFF Health News, “Federal Program To Save Rural Hospitals Feels ‘Growing Pains,’” Jan. 16, 2024.

Microsoft Teams interview, Shannon Wu, director of payment policy at the American Hospital Association, Oct. 1, 2024.

Zoom interview, Brock Slabach, chief operating officer, National Rural Health Association, Oct. 1, 2024.

Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, “Patterns of Hospital Bypass and Inpatient Care-Seeking by Rural Residents,” accessed Oct. 1, 2024.

Zoom interview, Harold Miller, president and CEO, Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, Sept. 26, 2024.

American Medical Association, “Issue Brief: Payment & Delivery in Rural Hospitals,” accessed Oct. 15, 2024.

Rural Health Information Hub, “Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs),” accessed Sept. 30, 2024.

KFF, “Medicare Advantage Enrollment, Plan Availability and Premiums in Rural Areas,” Sept. 7, 2023.

KFF Health News, “Tiny, Rural Hospitals Feel the Pinch as Medicare Advantage Plans Grow,” Oct. 23, 2023.

Email interview, James Swann, director of communications and public affairs, AHIP, Oct. 21, 2024.

Medicaid.gov, “Implementation Guide: Citizenship and Non-Citizen Eligibility,” accessed Oct. 10, 2024.

Zoom and email interview, Hayden Dublois, data and analytics director, the Foundation for Government Accountability, Oct. 1, 2024.

The Commonwealth Fund, “How Differences in Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial Health Insurance Payment Rates Impact Access, Health Equity, and Cost,” Aug. 17, 2022.

KFF Health News, “States Expand Health Coverage for Immigrants as GOP Hits Biden Over Border Crossings,” Dec. 28, 2023.

Phone interview, George Pink, deputy director, North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, Sept. 30, 2024.

KFF, “State Health Coverage for Immigrants and Implications for Health Coverage and Care,” May 1, 2024.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry Archives - KFF Health News