Assisted living centers have become an appealing retirement option for hundreds of thousands of boomers who can no longer live independently, promising a cheerful alternative to the institutional feel of a nursing home.

But their cost is so crushingly high that most Americans can’t afford them.

These highly profitable facilities often charge $5,000 a month or more and then layer on fees at every step. Residents’ bills and price lists from a dozen facilities offer a glimpse of the charges: $12 for a blood pressure check; $50 per injection (more for insulin); $93 a month to order medications from a pharmacy not used by the facility; $315 a month for daily help with an inhaler.

The facilities charge extra to help residents get to the shower, bathroom, or dining room; to deliver meals to their rooms; to have staff check-ins for daily “reassurance” or simply to remind residents when it’s time to eat or take their medication. Some even charge for routine billing of a resident’s insurance for care.

“They say, ‘Your mother forgot one time to take her medications, and so now you’ve got to add this on, and we’re billing you for it,’” said Lori Smetanka, executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, a nonprofit.

About 850,000 older Americans reside in assisted living facilities, which have become one of the most lucrative branches of the long-term care industry that caters to people 65 and older. Investors, regional companies, and international real estate trusts have jumped in: Half of operators in the business of assisted living earn returns of 20% or more than it costs to run the sites, an industry survey shows. That is far higher than the money made in most other health sectors.

Rents are often rivaled or exceeded by charges for services, which are either packaged in a bundle or levied à la carte. Overall prices have been rising faster than inflation, and rent increases since the start of last year have been higher than at any previous time since at least 2007, according to the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care, which provides data and other information to companies.

There are now 31,000 assisted living facilities nationwide — twice the number of skilled nursing homes. Four of every five facilities are run as for-profits. Members of racial or ethnic minority groups account for only a tenth of residents, even though they make up a quarter of the population of people 65 or older in the United States.

A public opinion survey conducted by KFF found that 83% of adults said it would be impossible or very difficult to pay $60,000 a year for an assisted living facility. Almost half of those surveyed who either lived in a long-term care residence or had a loved one who did encountered unexpected add-on fees for things they assumed were included in the price.

Assisted living is part of a broader affordability crisis in long-term care for the swelling population of older Americans. Over the past decade, the market for long-term care insurance has virtually collapsed, covering just a tiny portion of older people. Home health workers who can help people stay safely in their homes are generally poorly paid and hard to find.

And even older people who can afford an assisted living facility often find their life savings rapidly drained.

Unlike most residents of nursing homes, where care is generally paid for by Medicaid, the federal-state program for the poor and disabled, assisted living residents or their families usually must shoulder the full costs. Most centers require those who can no longer pay to move out.

The industry says its pricing structures pay for increased staffing that helps the more infirm residents and avoids saddling others with costs of services they don’t need.

Prices escalate greatly when a resident develops dementia or other serious illnesses. At one facility in California, the monthly cost of care packages for people with dementia or other cognitive issues increased from $1,325 for those needing the least amount of help to $4,625 as residents’ needs grew.

“It’s profiteering at its worst,” said Mark Bonitz, who explored multiple places in Minnesota for his mother, Elizabeth. “They have a fixed amount of rooms,” he said. “The way you make the most money is you get so many add-ons.” Last year, he moved his mother to a nonprofit center, where she lived until her death in July at age 96.

LaShuan Bethea, executive director of the National Center for Assisted Living, a trade association of owners and operators, said the industry would require financial support from the government and private lenders to bring prices down.

“Assisted living providers are ready and willing to provide more affordable options, especially for a growing elderly population,” Bethea said. “But we need the support of policymakers and other industries.” She said offering affordable assisted living “requires an entirely different business model.”

Others defend the extras as a way to appeal to the waves of boomers who are retiring. “People want choice,” said Beth Burnham Mace, a special adviser for the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care. “If you price it more à la carte, you’re paying for what you actually desire and need.”

Yet residents don’t always get the heightened attention they paid for. Class-action lawsuits have accused several assisted living chains of failing to raise staffing levels to accommodate residents’ needs or of failing to fulfill billed services.

“We still receive many complaints about staffing shortages and services not being provided as promised,” said Aisha Elmquist, until recently the deputy ombudsman for long-term care in Minnesota, a state-funded advocate. “Some residents have reported to us they called 911 for things like getting in and out of bed.”

‘Can You Find Me a Money Tree?’

Florence Reiners, 94, adores living at the Waters of Excelsior, an upscale assisted living facility in the Minneapolis suburb of Excelsior. The 115-unit building has a theater, a library, a hair salon, and a spacious dining room.

“The windows, the brightness, and the people overall are very cheerful and very friendly,” Reiners, a retired nursing assistant, said. Most important, she was just a floor away from her husband, Donald, 95, a retired water department worker who served in the military after World War II and has severe dementia.

She resisted her children’s pleas to move him to a less expensive facility available to veterans.

Reiners is healthy enough to be on a floor for people who can live independently, so her rent is $3,330 plus $275 for a pendant alarm. When she needs help, she’s billed an exact amount, like a $26.67 charge for the 31 minutes an aide spent helping her to the bathroom one night.

Her husband’s specialty care at the facility cost much more: $6,150 a month on top of $3,825 in rent.

Month by month, their savings, mainly from the sale of their home, and monthly retirement income of $6,600 from Social Security and his municipal pension, dwindled. In three years, their assets and savings dropped to about $300,000 from around $550,000.

Her children warned her that she would run out of money if her health worsened. “She about cried because she doesn’t want to leave her community,” Anne Palm, one of her daughters, said.

In June, they moved Donald Reiners to the VA home across the city. His care there costs $3,900 a month, 60% less than at the Waters. But his wife is not allowed to live at the veterans’ facility.

After nearly 60 years together, she was devastated. When an admissions worker asked her if she had any questions, she answered, “Can you find me a money tree so I don’t have to move him?”

Heidi Elliott, vice president for operations at the Waters, said employees carefully review potential residents’ financial assets with them, and explain how costs can increase over time.

“Oftentimes, our senior living consultants will ask, ‘After you’ve reviewed this, Mr. Smith, how many years do you think Mom is going to be able to, to afford this?’” she said. “And sometimes we lose prospects because they’ve realized, ‘You know what? Nope, we don’t have it.’”

Potential Buyers From the Bahamas

For residents, the median annual price of assisted living has increased 31% faster than inflation, nearly doubling from 2004 to 2021, to $54,000, according to surveys by the insurance firm Genworth. Monthly fees at memory care centers, which specialize in people with dementia and other cognitive issues, can exceed $10,000 in areas where real estate is expensive or the residents’ needs are high.

Diane Lepsig, president of CarePatrol of Bellevue-Eastside, in the Seattle suburbs, which helps place people, said that she has warned those seeking advice that they should expect to pay at least $7,000 a month. “A million dollars in assets really doesn’t last that long,” she said.

Prices rose even faster during the pandemic as wages and supply costs grew. Brookdale Senior Living, one of the nation’s largest assisted living owners and operators, reported to stockholders rate increases that were higher than usual for this year. In its assisted living and memory care division, Brookdale’s revenue per occupied unit rose 9.4% in 2023 from 2022, primarily because of rent increases, financial disclosures show.

In a statement, Brookdale said it worked with prospective residents and their families to explain the pricing and care options available: “These discussions begin in the initial stages of moving in but also continue throughout the span that one lives at a community, especially as their needs change.”

Many assisted living facilities are owned by real estate investment trusts. Their shareholders expect the high returns that are typically gained from housing investments rather than the more marginal profits of the heavily regulated health care sector. Even during the pandemic, earnings remained robust, financial filings show.

Ventas, a publicly traded real estate investment trust, reported earning revenues in the third quarter of this year that were 24% above operating costs from its investments in 576 senior housing properties, which include those run by Atria Senior Living and Sunrise Senior Living.

Ventas said the prices for its services were affordable. “In markets where we operate, on average it costs residents a comparable amount to live in our communities as it does to stay in their own homes and replicate services,” said Molly McEvily, a spokesperson.

In the same period, Welltower, another large real estate investment trust, reported a 24% operating margin from its 883 senior housing properties, which include ones operated by Sunrise, Atria, Oakmont Management Group, and Belmont Village. Welltower did not respond to requests for comment.

The median operating margin for assisted living facilities in 2021 was 23% if they offered memory care and 20% if they didn’t, according to David Schless, chief executive of the American Seniors Housing Association, a trade group that surveys the industry each year.

Bethea said those returns could be invested back into facilities’ services, technology, and building updates. “This is partly why assisted living also enjoys high customer satisfaction rates,” she said.

Brandon Barnes, an administrator at a family business that owns three small residences in Esko, Minnesota, said he and other small operators had been approached by brokers for companies, including one based in the Bahamas. “I don’t even know how you’d run them from that far away,” he said.

Rating the Cost of a Shower, on a Point Scale

To consistently get such impressive returns, some assisted living facilities have devised sophisticated pricing methods. Each service is assigned points based on an estimate of how much it costs in extra labor, to the minute. When residents arrive, they are evaluated to see what services they need, and the facility adds up the points. The number of points determines which tier of services you require; facilities often have four or five levels of care, each with its own price.

Charles Barker, an 81-year-old retired psychiatrist with Alzheimer’s, moved into Oakmont of Pacific Beach, a memory care facility in San Diego, in November 2020. In the initial estimate, he was assigned 135 points: 5 for mealtime reminders; 12 for shaving and grooming reminders; 18 for help with clothes selection twice a day; 36 to manage medications; and 30 for the attention, prompting, and redirection he would need because of his dementia, according to a copy of his assessment provided by his daughter, Celenie Singley.

Barker’s points fell into the second-lowest of five service levels, with a charge of $2,340 on top of his $7,895 monthly rent.

Singley became distraught over safety issues that she said did not seem as important to Oakmont as its point system. She complained in a May 2021 letter to Courtney Siegel, the company’s chief executive, that she repeatedly found the doors to the facility, located on a busy street, unlocked — a lapse at memory care centers, where secured exits keep people with dementia from wandering away. “Even when it’s expensive, you really don’t know what you’re getting,” she said in an interview.

Singley, 50, moved her father to another memory care unit. Oakmont did not respond to requests for comment.

Other residents and their families brought a class-action lawsuit against Oakmont in 2017 that said the company, an assisted living and memory care provider based in Irvine, California, had not provided enough staffing to meet the needs of residents it identified through its own assessments.

Jane Burton-Whitaker, a plaintiff who moved into Oakmont of Mariner Point in Alameda, California, in 2016, paid $5,795 monthly rent and $270 a month for assistance with her urinary catheter, but sometimes the staff would empty the bag just once a day when it required multiple changes, the lawsuit said.

She paid an additional $153 a month for checks of her “fragile” skin “up to three times a day, but most days staff did not provide any skin checks,” according to the lawsuit. (Skin breakdown is a hazard for older people that can lead to bedsores and infections.) Sometimes it took the staff 45 minutes to respond to her call button, so she left the facility in 2017 out of concern she would not get attention should she have a medical emergency, the lawsuit said.

Oakmont paid $9 million in 2020 to settle the class-action suit and agreed to provide enough staffing, without admitting fault.

Similar cases have been brought against other assisted living companies. In 2021, Aegis Living, a company based in Bellevue, Washington, agreed to a $16 million settlement in a case claiming that its point system — which charged 64 cents per point per day — was “based solely on budget considerations and desired profit margins.” Aegis did not admit fault in the settlement or respond to requests for comment.

When the Money Is Gone

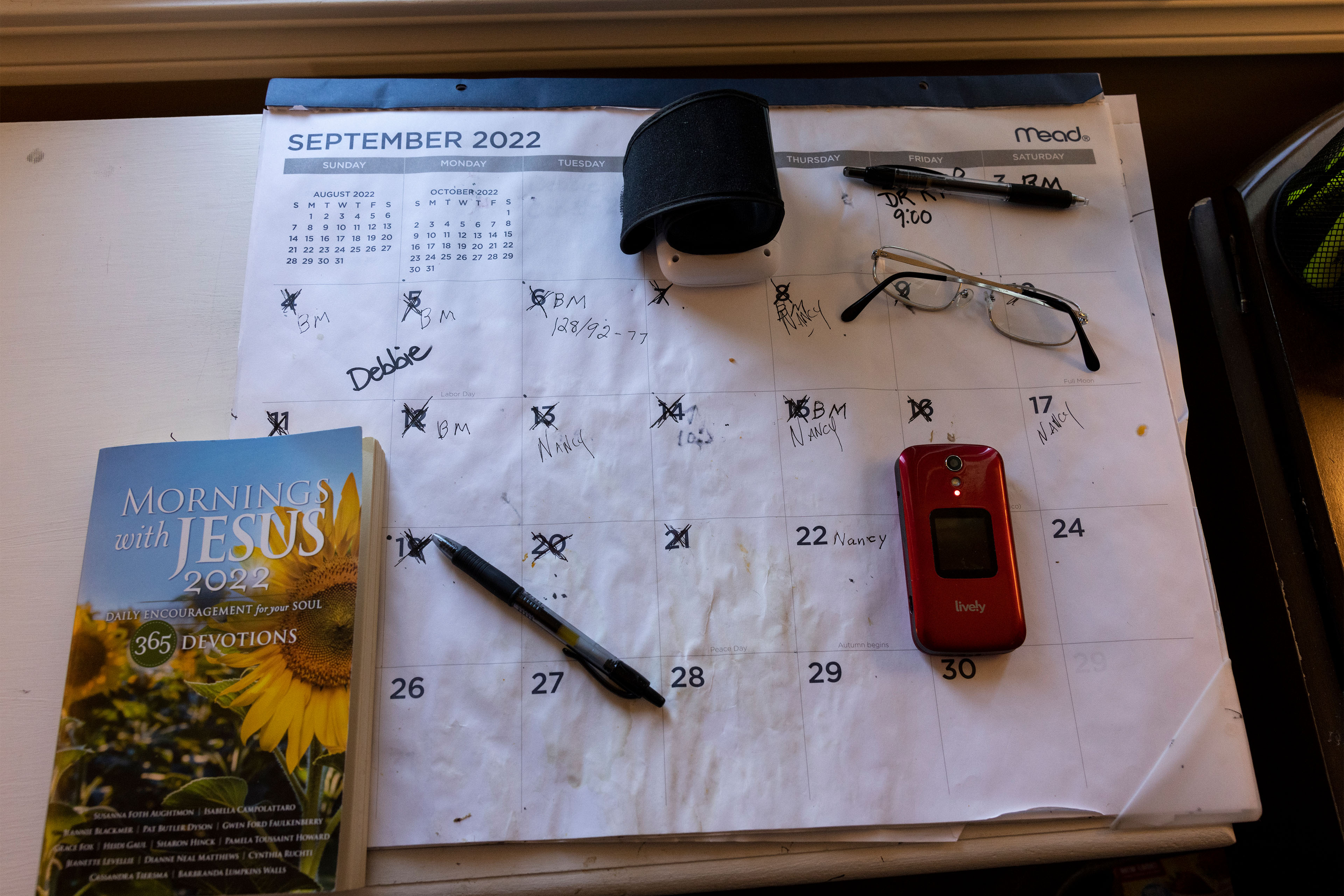

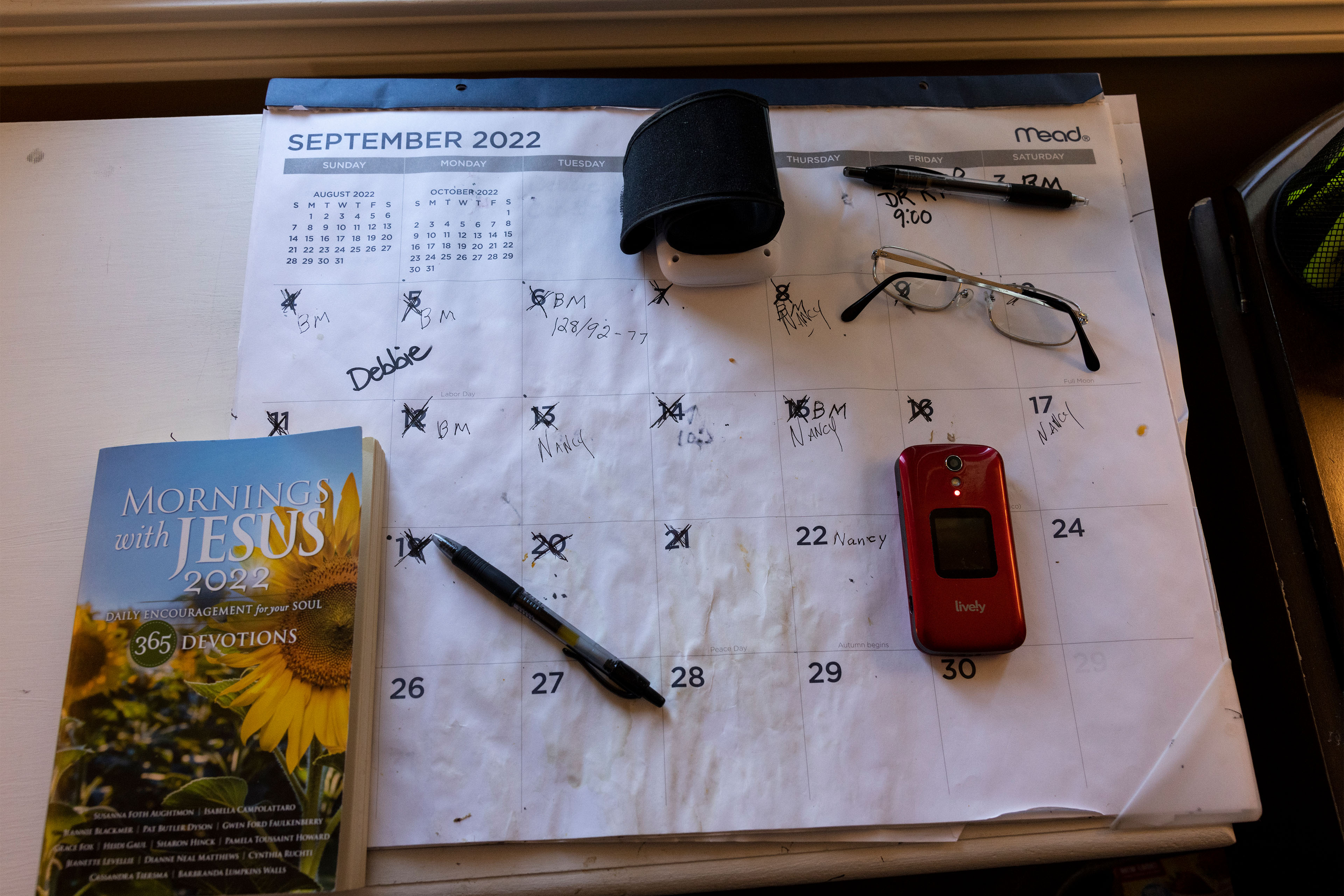

Jon Guckenberg’s rent for a single room in an assisted living cottage in rural Minnesota was $4,140 a month before adding in a raft of other charges.

The facility, New Perspective Cloquet, charged him $500 to reserve a spot and a $2,000 “entrance fee” before he set foot inside two years ago. Each month, he also paid $1,080 for a care plan that helped him cope with bipolar disorder and kidney problems, $750 for meals, and another $750 to make sure he took his daily medications. Cable service in his room was an extra $50 a month.

A year after moving in, Guckenberg, 83, a retired pizza parlor owner, had run through his life’s savings and was put on a state health plan for the poor.

Doug Anderson, a senior vice president at New Perspective, said in a statement that “the cost and complexity of providing care and housing to seniors has increased exponentially due to the pandemic and record-high inflation.”

In one way, Guckenberg has been luckier than most people who run out of money to pay for their care. His residential center accepts Medicaid to cover the health services he receives.

Most states have similar programs, though a resident must be frail enough to qualify for a nursing home before Medicaid will cover the health care costs in an assisted living facility. But enrollment is restricted. In 37 states, people are on waiting lists for months or years.

“We recognize the current system of having residents spend down their assets and then qualify for Medicaid in order to stay in their assisted living home is broken,” said Bethea, with the trade association. “Residents shouldn’t have to impoverish themselves in order to continue receiving assisted living care.”

Only 18% of residential care facilities agree to take Medicaid payments, which tend to be lower than what they charge self-paying clients, according to a federal survey of facilities. And even places that accept Medicaid often limit coverage to a minority of their beds.

For those with some retirement income, Medicaid isn’t free. Nancy Pilger, Guckenberg’s guardian, said that he was able to keep only about $200 of his $2,831 monthly retirement income, with the rest going to paying rent and a portion of his costs covered by the government.

In September, Guckenberg moved to a nearby assisted living building run by a nonprofit. Pilger said the price was the same. But for other residents who have not yet exhausted their assets, Guckenberg’s new home charges $12 a tray for meal delivery to the room; $50 a month to bill a person’s long-term care insurance plan; and $55 for a set of bed rails.

Even after Guckenberg had left New Perspective, however, the company had one more charge for him: a $200 late payment fee for money it said he still owed.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry Archives - KFF Health News