After HCA Healthcare announced this month that the personal identification data of roughly 11 million HCA patients in 20 states had been exposed in a breach, people may be justifiably concerned that their own medical data and identities could be stolen.

Consumers should realize that such “medical identity” fraud can happen in several ways, from a large-scale breach to individual theft of someone’s data.

Just ask Evelyn Miller. The first sign something was amiss was a text Miller received from an Emory University Hospital emergency department informing her that her wait time to be seen was 30 minutes to 1 hour. That’s weird, she thought. She no longer lives in Atlanta and hadn’t used that hospital system in years. Then she got a second text, similar to the first. Must be spam, she thought.

When she got a call the next day from an Emory staffer named Michael to discuss the diagnostic results from her ER visit, she knew something was definitely wrong. “It amazed me someone could get registered with another person’s name and no ID was checked or anything,” Miller said.

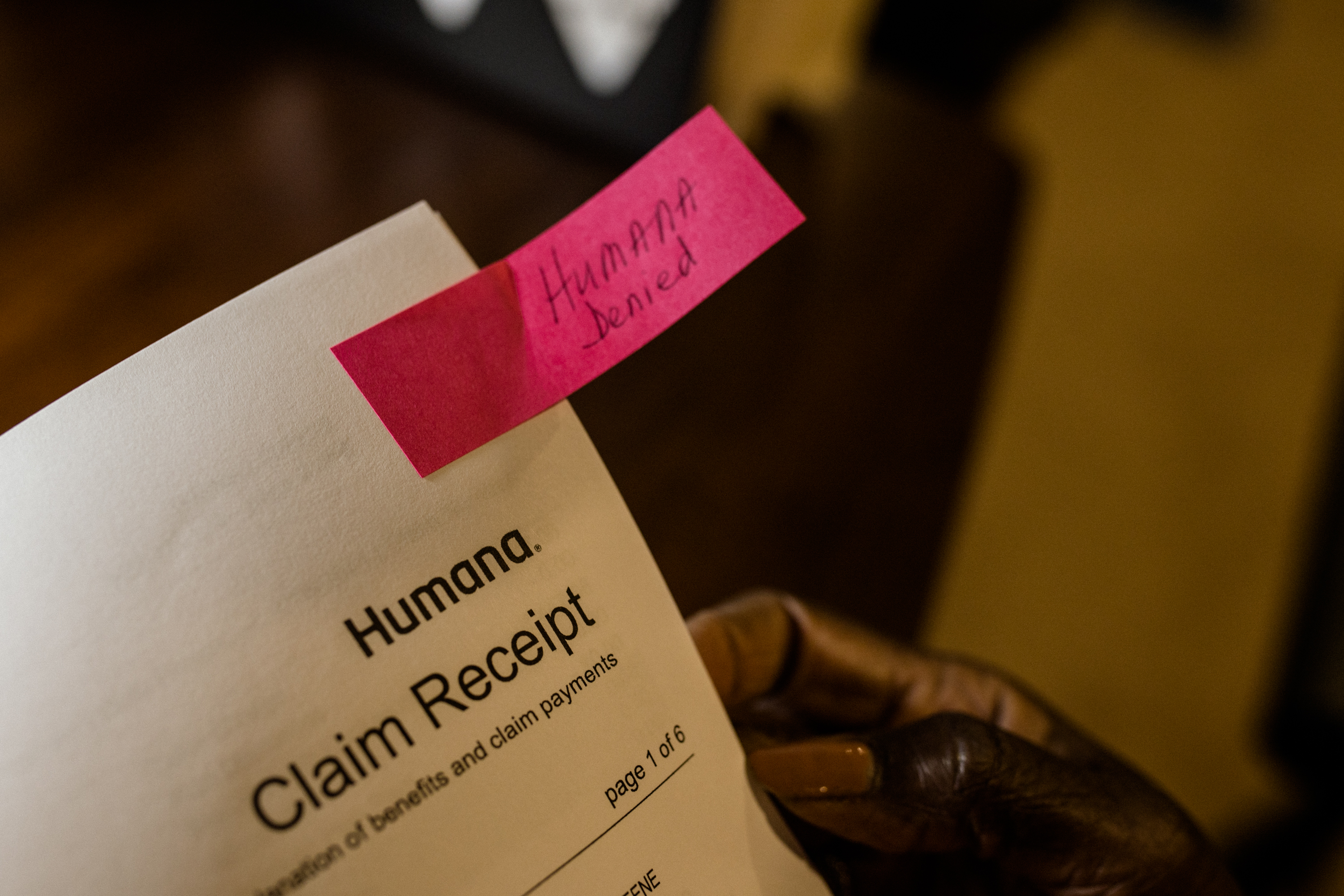

And while the name and date of birth the staffer had on record for her were correct, Miller’s address was not. She now lives in Blairsville, Georgia, a few hours north of Atlanta. Michael said he’d correct the problem. The next week, she got a bill from Emory for more than $3,600.

After an unsatisfactory conversation with someone in the hospital’s billing department, Miller sent a letter to the hospital’s privacy officer. Miller recalled writing: “I think there’s something going on, that someone is using my information, and the visit and the charges appear to be fraudulent.”

When contacted, Emory Healthcare spokesperson Janet Christenbury declined to comment on Miller’s case specifically but did say, “We take these matters seriously and work with our teams to ensure our processes and procedures are followed.”

Miller, 63, a retired health care administrator, was savvier than many about what might have occurred. The average person may have no idea a problem like this can arise until long after a theft occurs.

“The majority of victims find out when they’re trying to move on with their lives, if bills have gone to collections,” said Eva Velasquez, president and CEO of the Identity Theft Resource Center, a nonprofit that provides free assistance to victims of identity theft. Someone may apply for a mortgage, for example, and learn their credit is ruined due to unpaid medical bills for care they didn’t receive.

It’s a double whammy. Unlike other forms of identity fraud, medical identity thieves may steal not only their victims’ personal data — Social Security number, date of birth, address — but also information about their medical records and care, potentially putting their health at risk.

“Sometimes people can’t get their prescriptions, if their records are mixed with someone else’s,” Velasquez said. “Maybe you won’t be able to get treatment that you need. There are serious implications.”

A theft may affect just one person whose insurance card gets stolen or “borrowed” to pay for health care, or it may result from a data breach, as HCA Healthcare experienced. Such large-scale breaches are more likely to be used in financial fraud schemes than to get medical care, experts say.

Compared with other types of identity fraud, medical identity theft is rare. In 2022, for example, the Federal Trade Commission received 27,821 reports of medical identity theft, while reports for identity theft related to new credit card accounts totaled more than 400,000.

Medical identity theft also presents itself in different ways.

One Thief, One Victim

If someone gets ahold of another person’s health insurance number and driver’s license or other ID, they may be able to use it to receive medical services in someone else’s name.

Busy hospital emergency departments may make an attractive target for fraudsters. Procedures typically require patients to present insurance and photo identification information at check-in, said Rade Vukmir, an emergency physician in Pittsburgh and a spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians. But these facilities also don’t want to put people off from getting care, and people who are uninsured or disadvantaged might not have those documents.

“We want to treat that population,” he said. “We’re America’s safety net. We always provide care.”

Medical identity theft can happen if someone loses a wallet with their insurance card in it, for example, or a piece of mail from their insurer goes astray. But it doesn’t occur only among strangers. The victim often knows the thief and may even be in on the “friendly fraud,” as it’s called. According to one study, nearly half of people who failed to report medical identity theft said it was because they knew the thief.

For example, one person might have a higher copayment for emergency department visits, Vukmir said, so they let a family member, such as a cousin or a sibling, use their insurance card to get medical care.

“Usually, in those cases, it wasn’t an emergency,” said Vukmir.

Gangs of Thieves, Millions of Victims

In 2022, 707 health care data breaches affected nearly 52 million patients, according to an analysis of data from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights by the HIPAA Journal, which tracks compliance with health care data privacy law. Under federal law, health care organizations must notify individuals when their medical data has been exposed through a breach.

The largest health care data breach to date occurred in 2015, when nearly 80 million Anthem records were exposed. Though the 2022 figures for incidents among all health plans were slightly lower than the year before, there has been a clear upward trend in recent years in breaches, which are typically caused by hacking or IT incidents.

The American Hospital Association is “very concerned” about foreign-based hacking groups from countries like Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran, said John Riggi, the national adviser for cybersecurity and risk for the American Hospital Association.

Riggi said the personal information in people’s medical records may be sold in bulk to criminals who create phony providers to submit fraudulent claims on a mass scale that can result in hundreds of millions of dollars in Medicaid, Medicare, or other insurance fraud. Or they may use the information to create fake identities to apply for loans, mortgages, or credit cards.

“They flee with the money, and the individual is left to deal with it,” Riggi said.

Health plans could take lessons from the financial services industry to detect red flags, Riggi said. Financial institutions have sophisticated algorithms to identify purchasing and other patterns that are out of the ordinary, Riggi said. In health care, such mechanisms could be used to flag claims in which a provider is located more than 1,000 miles from where a patient lives, for example, or sees a patient for conditions that don’t jibe with their age or health status.

AHIP, an insurance industry trade group, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

What Consumers Can Do

Consumers should generally monitor the notices and bills they receive from insurers and providers and contact them immediately about anything suspicious.

In Miller’s case, it’s unclear whether her problem was due to an administrative snafu, such as another patient with the same name, or medical identity theft. But within a month of her initial call, the hospital removed the charges and assured her that her medical record had been disentangled from the other patient’s.

Other steps to take:

- Go to the FTC’s identity theft site to learn about next steps and file an identity theft report, if appropriate.

- If someone has used your name, contact every provider who may have been involved and ask for a copy of your medical records, then report any errors to your medical providers.

- Notify your health plan’s fraud department and send a copy of the FTC identity theft report.

- File free fraud alerts with the three major credit reporting agencies and get free credit reports from them. Consider filing a police report. If your health plan offers free credit or identity theft monitoring following a breach, take advantage of it.

“It’s best to proceed as if your data has been compromised and will be for sale,” said Velasquez, whose organization offers free assistance in recovering from identity theft. “Don’t be afraid to ask for help.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry – KFF Health News