Two-year-old Zion Gastelum died just days after dentists performed root canals and put crowns on six baby teeth at a clinic affiliated with a private equity firm.

His parents sued the Kool Smiles dental clinic in Yuma, Arizona, and its private equity investor, FFL Partners. They argued the procedures were done needlessly, in keeping with a corporate strategy to maximize profits by overtreating kids from lower-income families enrolled in Medicaid. Zion died after being diagnosed with “brain damage caused by a lack of oxygen,” according to the lawsuit.

Kool Smiles “overtreats, underperforms and overbills,” the family alleged in the suit, which was settled last year under confidential terms. FFL Partners and Kool Smiles had no comment but denied liability in court filings.

Private equity is rapidly moving to reshape health care in America, coming off a banner year in 2021, when the deep-pocketed firms plowed $206 billion into more than 1,400 health care acquisitions, according to industry tracker PitchBook.

Seeking quick returns, these investors are buying into eye care clinics, dental management chains, physician practices, hospices, pet care providers, and thousands of other companies that render medical care nearly from cradle to grave. Private equity-backed groups have even set up special “obstetric emergency departments” at some hospitals, which can charge expectant mothers hundreds of dollars extra for routine perinatal care.

As private equity extends its reach into health care, evidence is mounting that the penetration has led to higher prices and diminished quality of care, a KHN investigation has found. KHN found that companies owned or managed by private equity firms have agreed to pay fines of more than $500 million since 2014 to settle at least 34 lawsuits filed under the False Claims Act, a federal law that punishes false billing submissions to the federal government with fines. Most of the time, the private equity owners have avoided liability.

New research by the University of California-Berkeley has identified “hot spots” where private equity firms have quietly moved from having a small foothold to controlling more than two-thirds of the market for physician services such as anesthesiology and gastroenterology in 2021. And KHN found that in San Antonio, more than two dozen gastroenterology offices are controlled by a private equity-backed group that billed a patient $1,100 for her share of a colonoscopy charge — about three times what she paid in another state.

It’s not just prices that are drawing scrutiny.

Whistleblowers and injured patients are turning to the courts to press allegations of misconduct or other improper business dealings. The lawsuits allege that some private equity firms, or companies they invested in, have boosted the bottom line by violating federal false claims and anti-kickback laws or through other profit-boosting strategies that could harm patients.

“Their model is to deliver short-term financial goals and in order to do that you have to cut corners,” said Mary Inman, an attorney who represents whistleblowers.

Federal regulators, meanwhile, are almost blind to the incursion, since private equity typically acquires practices and hospitals below the regulatory radar. KHN found that more than 90% of private equity takeovers or investments fall below the $101 million threshold that triggers an antitrust review by the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Justice Department.

Spurring Growth

Private equity firms pool money from investors, ranging from wealthy people to college endowments and pension funds. They use that money to buy into businesses they hope to flip at a sizable profit, usually within three to seven years, by making them more efficient and lucrative.

Private equity has poured nearly $1 trillion into nearly 8,000 health care transactions during the past decade, according to PitchBook.

Fund managers who back the deals often say they have the expertise to reduce waste and turn around inefficient, or moribund, businesses, and they tout their role in helping to finance new drugs and technologies expected to benefit patients in years to come.

Critics see a far less rosy picture. They argue that private equity’s playbook, while it may work in some industries, is ill suited for health care, when people’s lives are on the line.

In the health care sphere, private equity has tended to find legal ways to bill more for medical services: trimming services that don’t turn a profit, cutting staff, or employing personnel with less training to perform skilled jobs — actions that may put patients at risk, critics say.

KHN, in a series of articles published this year, has examined a range of private equity forays into health care, from its marketing of America’s top-selling emergency contraception pill to buying up whole chains of ophthalmology and gastroenterology practices and investing in the booming hospice care industry and even funeral homes.

These deals happened on top of well-publicized takeovers of hospital emergency room staffing firms that led to outrageous “surprise” medical bills for some patients, as well as the buying up of entire rural hospital systems.

“Their only goal is to make outsize profits,” said Laura Olson, a political science professor at Lehigh University and a critic of the industry.

Hot Spots

When it comes to acquisitions, private equity firms have similar appetites, according to a KHN analysis of 600 deals by the 25 firms that PitchBook says have most frequently invested in health care.

Eighteen of the firms have dental companies listed in their portfolios, and 16 list centers that offer treatment of cataracts, eye surgery, or other vision care, KHN found.

Fourteen have bought stakes in animal hospitals or pet care clinics, a market in which rapid consolidation led to a recent antitrust action by the FTC. The agency reportedly also is investigating whether U.S. Anesthesia Partners, which operates anesthesia practices in nine states, has grown too dominant in some areas.

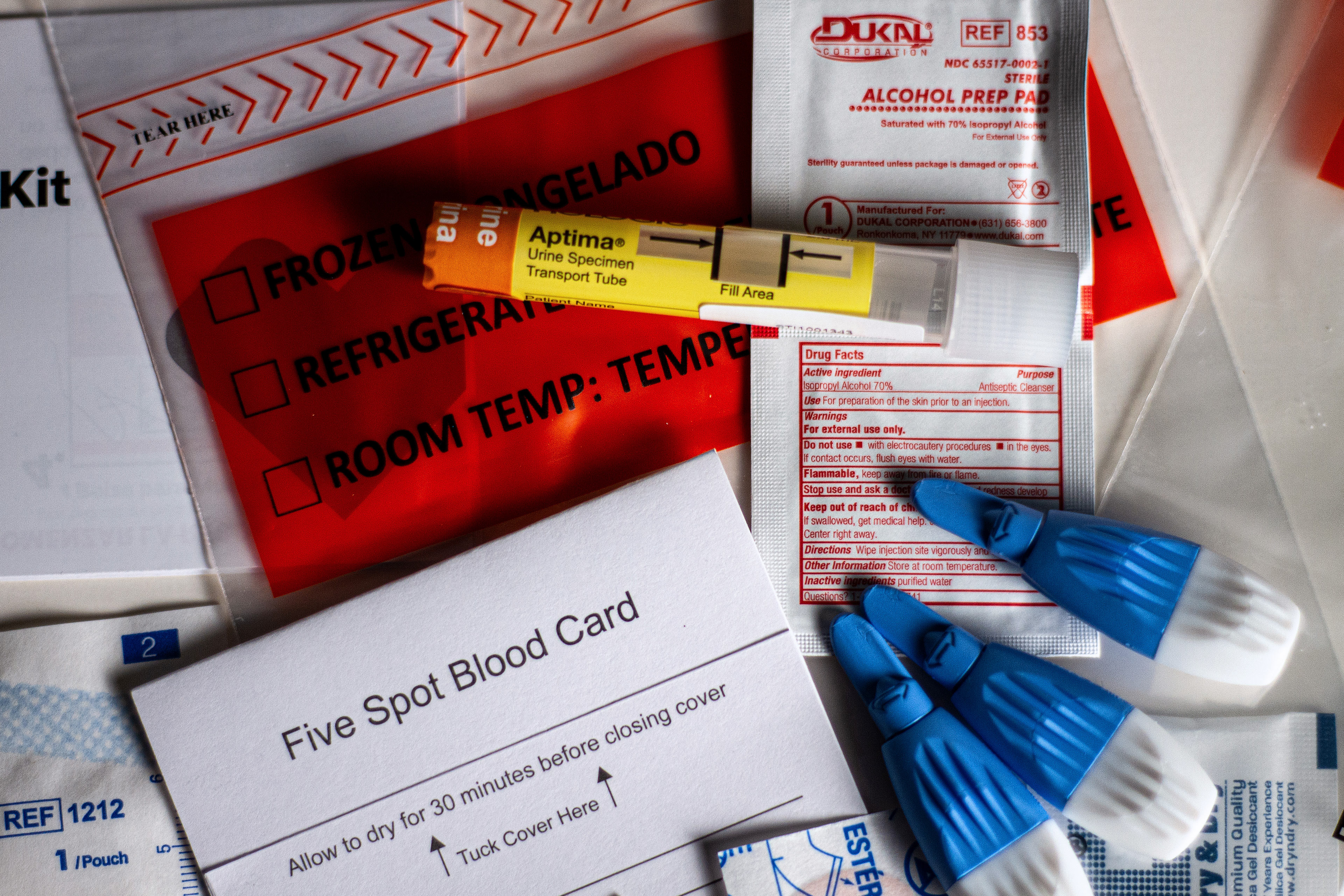

Private equity has flocked to companies that treat autism, drug addiction, and other behavioral health conditions. The firms have made inroads into ancillary services such as diagnostic and urine-testing and software for managing billing and other aspects of medical practice.

Private equity has done so much buying that it now dominates several specialized medical services, such as anesthesiology and gastroenterology, in a few metropolitan areas, according to new research made available to KHN by the Nicholas C. Petris Center at UC-Berkeley.

Although private equity plays a role in just 14% of gastroenterology practices nationwide, it controls nearly three-quarters of the market in at least five metropolitan areas across five states, including Texas and North Carolina, according to the Petris Center research.

Similarly, anesthesiology practices tied to private equity hold 12% of the market nationwide but have swallowed up more than two-thirds of it in parts of five states, including the Orlando, Florida, area, according to the data.

These expansions can lead to higher prices for patients, said Yashaswini Singh, a researcher at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University.

In a study of 578 physician practices in dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology published in JAMA Health Forum in September, Singh and her team tied private equity takeovers to an average increase of $71 per medical claim filed and a 9% increase in lengthy, more costly, patient visits.

Singh said in an interview that private equity may develop protocols that bring patients back to see physicians more often than in the past, which can drive up costs, or order more lucrative medical services, whether needed or not, that boost profits.

“There are more questions than answers,” Singh said. “It really is a black hole.”

Jean Hemphill, a Philadelphia health care attorney, said that in some cases private equity has merely taken advantage of the realities of operating a modern medical practice amid growing administrative costs.

Physicians sometimes sell practices to private equity firms because they promise to take over things like billing, regulatory compliance, and scheduling — allowing doctors to focus on practicing medicine. (The physicians also might reap a big payout.)

“You can’t do it on a scale like Marcus Welby used to do it,” Hemphill said, referring to an early 1970s television drama about a kindly family doctor who made house calls. “That’s what leads to larger groups,” she said. “It is a more efficient way to do it.”

But Laura Alexander, a former vice president of policy at the nonprofit American Antitrust Institute, which collaborated on the Petris Center research, said she is concerned about private equity’s growing dominance in some markets.

“We’re still at the stage of understanding the scope of the problem,” Alexander said. “One thing is clear: Much more transparency and scrutiny of these deals is needed.”

‘Revenue Maximization’

Private equity firms often bring a “hands-on” approach to management, taking steps such as placing their representatives on a company’s board of directors and influencing the hiring and firing of key staffers.

“Private equity exercises immense control over the operations of health care companies it buys an interest in,” said Jeanne Markey, a Philadelphia whistleblower attorney.

Markey represented physician assistant Michelle O’Connor in a 2015 whistleblower lawsuit filed against National Spine and Pain Centers and its private equity owner, Sentinel Capital Partners.

In just a year under private equity guidance, National Spine’s patient load quadrupled as it grew into one of the nation’s largest pain management chains, treating more than 160,000 people in about 40 offices across five East Coast states, according to the suit.

O’Connor, who worked at two National Spine clinics in Virginia, said the mega-growth strategy sprang from a “corporate culture in which money trumps the provision of appropriate patient care,” according to the suit.

She cited a “revenue maximization” policy that mandated medical staffers see at least 25 patients a day, up from 16 to 18 before the takeover.

The pain clinics also overcharged Medicare by billing up to $1,100 for “unnecessary and often worthless” back braces and charging up to $1,800 each for urine drug tests that were “medically unnecessary and often worthless,” according to the suit.

In April 2019, National Spine paid the Justice Department $3.3 million to settle the whistleblower’s civil case without admitting wrongdoing.

Sentinel Capital Partners, which by that time had sold the pain management chain to another private equity firm, paid no part of National Spine’s settlement, court records show. Sentinel Capital Partners had no comment.

In another whistleblower case, a South Florida pharmacy owned by RLH Equity Partners raked in what the lawsuit called an “extraordinarily high” profit on more than $68 million in painkilling and scar creams billed to the military health insurance plan Tricare.

The suit alleges that the pharmacy paid illegal kickbacks to telemarketers who drove the business. One doctor admitted prescribing the creams to scores of patients he had never seen, examined, or even spoken to, according to the suit.

RLH, based in Los Angeles, disputed the Justice Department’s claims. In 2019, RLH and the pharmacy paid a total of $21 million to settle the case. Neither admitted liability. RLH managing director Michel Glouchevitch told KHN that his company cooperated with the investigation and that “the individuals responsible for any problems have been terminated.”

In many fraud cases, however, private equity investors walk away scot-free because the companies they own pay the fines. Eileen O’Grady, a researcher at the nonprofit Private Equity Stakeholder Project, said government should require “added scrutiny” of private equity companies whose holdings run afoul of the law.

“Nothing like that exists,” she said.

Questions About Quality

Whether private equity influences the quality of medical care is tough to discern.

Robert Homchick, a Seattle health care regulatory attorney, said private equity firms “vary tremendously” in how conscientiously they manage health care holdings, which makes generalizing about their performance difficult.

“Private equity has some bad actors, but so does the rest of the [health care] industry,” he said. “I think it’s wrong to paint them all with the same brush.”

But incipient research paints a disturbing picture, which took center stage earlier this year.

On the eve of President Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech in March, the White House released a statement that accused private equity of "buying up struggling nursing homes” and putting “profits before people.”

The covid-19 pandemic had highlighted the “tragic impact” of staffing cuts and other moneysaving tactics in nursing homes, the statement said.

More than 200,000 nursing home residents and staffers had died from covid in the previous two years, according to the White House, and research had linked private equity to inflated nursing costs and elevated patient death rates.

Some injured patients are turning to the courts in hopes of holding the firms accountable for what the patients view as lapses in care or policies that favor profits over patients.

Dozens of lawsuits link patient harm to the sale of Florida medical device maker Exactech to TPG Capital, a Texas private equity firm. TPG acquired the device company in February 2018 for about $737 million.

In August 2021, Exactech recalled its Optetrak knee replacement system, warning that a defect in packaging might cause the implant to loosen or fracture and cause “pain, bone loss or recurrent swelling.” In the lawsuits, more than three dozen patients accuse Exactech of covering up the defects for years, including, some suits say, when “full disclosure of the magnitude of the problem … might have negatively impacted” Exactech’s sale to TPG.

Linda White is suing Exactech and TPG, which she asserts is “directly involved” in the device company’s affairs.

White had Optetrak implants inserted into both her knees at a Galesburg, Illinois, hospital in June 2012. The right one failed and was replaced with a second Optetrak implant in July 2015, according to her lawsuit. That one also failed, and she had it removed and replaced with a different company’s device in January 2019.

The Exactech implant in White’s left knee had to be removed in May 2019, according to the suit, which is pending in Cook County Circuit Court in Illinois.

In a statement to KHN, Exactech said it conducted an “extensive investigation” when it received reports of “unexpected wear of our implants.”

Exactech said the problem dated to 2005 but was discovered only in July of last year. “Exactech disputes the allegations in these lawsuits and intends to vigorously defend itself,” the statement said. TPG declined to comment but has denied the allegations in court filings.

‘Invasive Procedures’

In the past, private equity business tactics have been linked to scandalously bad care at some dental clinics that treated children from low-income families.

In early 2008, a Washington, D.C., television station aired a shocking report about a local branch of the dental chain Small Smiles that included video of screaming children strapped to straightjacket-like “papoose boards” before being anesthetized to undergo needless operations like baby root canals.

Five years later, a U.S. Senate report cited the TV exposé in voicing alarm at the "corporate practice of dentistry in the Medicaid program.” The Senate report stressed that most dentists turned away kids enrolled in Medicaid because of low payments and posed the question: How could private equity make money providing that care when others could not?

“The answer is ‘volume,’” according to the report.

Small Smiles settled several whistleblower cases in 2010 by paying the government $24 million. At the time, it was providing “business management and administrative services” to 69 clinics nationwide, according to the Justice Department. It later declared bankruptcy.

But complaints that volume-driven dentistry mills have harmed disadvantaged children didn’t stop.

According to the 2018 lawsuit filed by his parents, Zion Gastelum was hooked up to an oxygen tank after questionable root canals and crowns “that was empty or not operating properly” and put under the watch of poorly trained staffers who didn’t recognize the blunder until it was too late.

Zion never regained consciousness and died four days later at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, the suit states. The cause of death was “undetermined,” according to the Maricopa County medical examiner’s office. An Arizona state dental board investigation later concluded that the toddler’s care fell below standards, according to the suit.

Less than a month after Zion’s death in December 2017, the dental management company Benevis LLC and its affiliated Kool Smiles clinics agreed to pay the Justice Department $24 million to settle False Claims Act lawsuits. The government alleged that the chain performed “medically unnecessary” dental services, including baby root canals, from January 2009 through December 2011.

In their lawsuit, Zion’s parents blamed his death on corporate billing policies that enforced “production quotas for invasive procedures such as root canals and crowns” and threatened to fire or discipline dental staff “for generating less than a set dollar amount per patient.”

Kool Smiles billed Medicaid $2,604 for Zion’s care, according to the suit. FFL Partners did not respond to requests for comment. In court filings, it denied liability, arguing it did not provide “any medical services that harmed the patient.”

Covering Tracks

Under a 1976 federal law called the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, deal-makers must report proposed mergers to the FTC and the Justice Department antitrust division for review. The intent is to block deals that stifle competition, which can lead to higher prices and lower-quality services.

But there’s a huge blind spot, which stymies government oversight of more than 90% of private equity investments in health care companies: The current threshold for reporting deals is $101 million.

KHN’s analysis of PitchBook data found that just 423 out of 7,839 private equity health care deals from 2012 through 2021 were known to have exceeded the current threshold.

In some deals, private equity takes a controlling interest in medical practices, and doctors work for the company. In other cases, notably in states whose laws prohibit corporate ownership of physician practices, the private equity firm handles a range of management duties.

Thomas Wollmann, a University of Chicago researcher, said antitrust authorities may not learn of consequential transactions “until long after they have been completed” and “it's very hard to break them up after the fact.”

In August, the FTC took aim at what it called “a growing trend toward consolidation” by veterinary medicine chains.

The FTC ordered JAB Consumer Partners, a private equity firm based in Luxembourg, to divest from some clinics in the San Francisco Bay and Austin, Texas, areas as part of a proposed $1.1 billion takeover of a rival.

The FTC said the deal would eliminate “head-to-head” competition, “increasing the likelihood that customers are forced to pay higher prices or experience a degradation in quality of the relevant services.”

Under the order, JAB must obtain FTC approval before buying veterinary clinics within 25 miles of the sites it owns in Texas and California.

The FTC would not say how much market consolidation is too much or whether it plans to step up scrutiny of health care mergers and acquisitions.

“Every case is fact-specific,” Betsy Lordan, an FTC spokesperson, told KHN.

Lordan, who has since left the agency, said regulators are considering updates to regulations governing mergers and are reviewing about 1,900 responses to the January 2022 request for public comment. At least 300 of the comments were from doctors or other health care workers.

Few industry observers expect the concerns to abate; they might even increase.

Investors are flush with “dry powder,” industry parlance for money waiting to stoke a deal.

The Healthcare Private Equity Association, which boasts about 100 investment companies as members, says the firms have $3 trillion in assets and are pursuing a vision for "building the future of healthcare.”

That kind of talk alarms Cornell University professor Rosemary Batt, a longtime critic of private equity. She predicts that investors chasing outsize profits will achieve their goals by “sucking the wealth” out of more and more health care providers.

“They are constantly looking for new financial tricks and strategies,” Batt said.

KHN’s Megan Kalata contributed to this article.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry – Kaiser Health News