Elizabeth Woodruff tuvo que usar los ahorros de su jubilación y buscar tres trabajos luego que ella y su esposo fueran demandados por casi $10,000 por un hospital de Nueva York, en donde al hombre le amputaron una pierna infectada.

Ariane Buck, un joven padre de Arizona que vende seguros de salud, no pudo hacer una cita con su médico por una seria infección intestinal porque en la consulta le dijeron que tenía facturas pendientes.

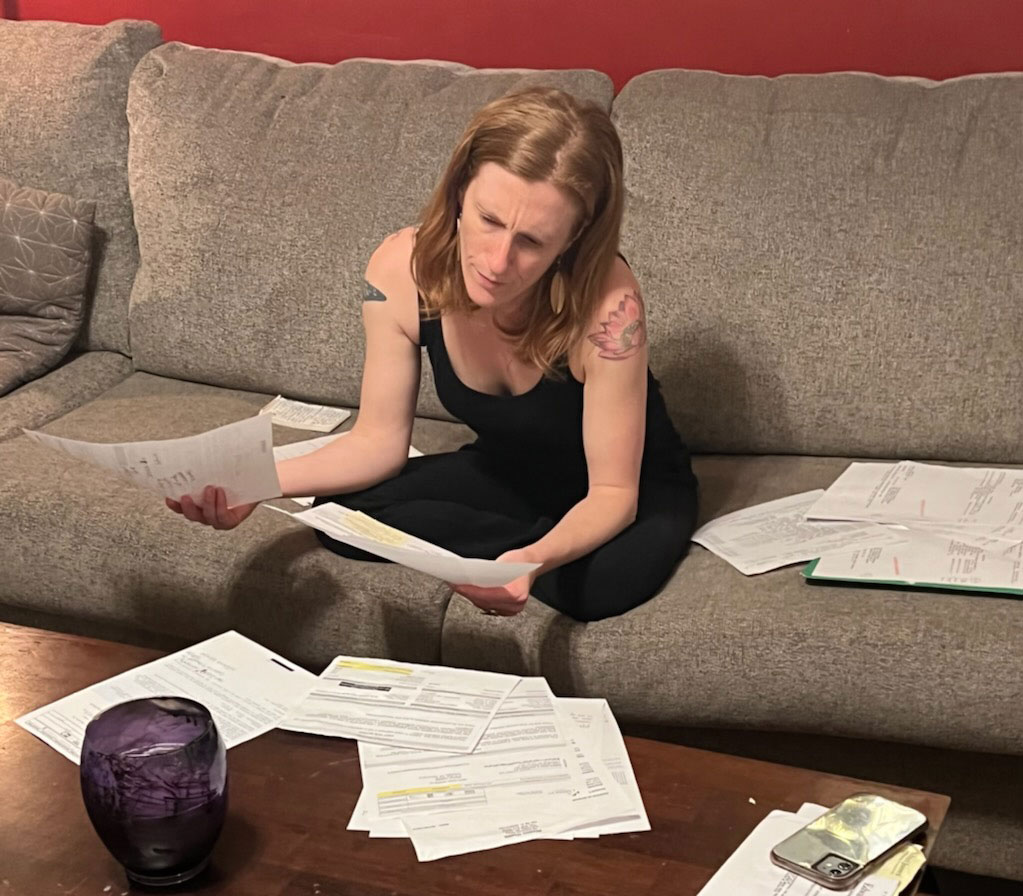

Allyson Ward y su marido cargaron las tarjetas de crédito, pidieron prestado a familiares y retrasaron el pago de los préstamos estudiantiles después de que el nacimiento prematuro de sus gemelos les dejara una deuda de $80,000. Ward, que es enfermera, se vio obligada a hacer turnos extra, trabajando día y noche.

“Quería ser madre”, dijo. “Pero teníamos que disponer de dinero”.

Estas personas se encuentran entre los más de 100 millones de estadounidenses —incluyendo el 41% de los adultos— acosados por un sistema de salud que endeuda sistemáticamente a los pacientes a escala masiva, según muestra una investigación de KHN y NPR.

La investigación revela un problema que, a pesar de la nueva atención prestada por la Casa Blanca y el Congreso, está mucho más extendido de lo que se había informado anteriormente. Esto se debe a que gran parte de la deuda que acumulan los pacientes figura como saldos de tarjetas de crédito, préstamos familiares o planes de pago a hospitales y otros proveedores médicos.

Para calcular el verdadero alcance y la carga de esta deuda, la investigación de KHN-NPR se basó en una encuesta nacional realizada por KFF para este proyecto. La encuesta fue diseñada para captar no solo las facturas que los pacientes no podían pagar, sino también otros préstamos utilizados para pagar la atención médica.

El proyecto también se nutre de los nuevos análisis de la oficina de crédito, la facturación de los hospitales y los datos de las tarjetas de crédito realizados por el Urban Institute y otros colaboradores de la investigación. Además, los reporteros de KHN y NPR realizaron cientos de entrevistas con pacientes, médicos, líderes del sector sanitario, defensores de los consumidores e investigadores.

El panorama es desolador.

En los últimos cinco años, más de la mitad de los adultos estadounidenses afirman haberse endeudado a causa de facturas médicas o dentales, según la encuesta de KFF.

Una cuarta parte de los adultos con deudas de atención de salud debe más de $5,000. Y aproximadamente 1 de cada 5 con una deuda dijo que no esperaba poder pagarla nunca.

"La deuda ya no es solo un error en nuestro sistema. Es uno de los principales productos", dijo el doctor Rishi Manchanda, que ha trabajado con pacientes de bajos ingresos en California durante más de una década y ha formado parte de la junta directiva de la organización sin fines de lucro RIP Medical Debt. "Tenemos un sistema de salud casi perfectamente diseñado para crear deuda".

Esta carga hace que las familias recorten el gasto en alimentos y otros productos esenciales. Millones de personas se ven obligadas a dejar sus hogares o a declararse en quiebra, halló la encuesta.

La deuda médica provoca dificultades adicionales para las personas con cáncer y otras enfermedades crónicas. Los niveles de deuda en los condados de Estados Unidos con las tasas más altas de enfermedad pueden ser tres o cuatro veces superiores a los de los condados más sanos, según un análisis del Urban Institute.

La deuda también agranda las disparidades raciales.

Y está impidiendo que los estadounidenses ahorren para la jubilación, inviertan en la educación de sus hijos o pongan los cimientos tradicionales para un futuro seguro, como pedir un préstamo para la universidad o comprar una casa. Según la encuesta de KFF, las deudas por atención médica son casi el doble de frecuentes entre los adultos menores de 30 años que entre los mayores de 65.

Tal vez lo más perverso sea que la deuda impide a los pacientes recibir atención médica.

Alrededor de 1 de cada 7 personas con deudas dijo que se le había negado el acceso a un hospital, a un médico o a otro proveedor debido a las facturas impagas, según la encuesta. Una proporción aún mayor —alrededor de dos tercios— ha pospuesto la atención que ellos o un miembro de la familia necesitan debido al costo.

"Es una barbaridad", afirmó la doctora Miriam Atkins, oncóloga de Georgia que, como muchos médicos, dijo que ha tenido pacientes que han renunciado al tratamiento por miedo a la deuda.

La deuda de los pacientes se acumula a pesar de la histórica Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA) de 2010.

ACA amplió la cobertura de seguro a decenas de millones de estadounidenses. Sin embargo, también marcó el comienzo de años de grandes beneficios para la industria médica, que ha aumentado constantemente los precios en la última década.

Los hospitales registraron su año más rentable de la historia en 2019, anotando un margen de beneficio agregado del 7,6%, según el Comité Asesor de Pagos de Medicare federal. Muchos hospitales prosperaron incluso durante la pandemia.

Pero para muchos estadounidenses, la ley no cumplió su promesa de una atención más asequible. En su lugar, han tenido que hacer frente a miles de dólares en facturas, ya que las aseguradoras transfirieron los costos a los pacientes a través de deducibles más altos.

Ahora, una industria muy lucrativa se aprovecha de la incapacidad de los pacientes para pagar.

Los hospitales y otros proveedores de servicios médicos ponen a millones de personas en manos de las tarjetas de crédito y otros préstamos. Y los pacientes sufren altas tasas de interés, al tiempo que generan beneficios para los prestamistas que superan el 29%, según la empresa de investigación IBISWorld.

Las deudas de los pacientes también sostienen un oscuro negocio de cobros alimentado por los hospitales —incluidos los sistemas universitarios públicos y las organizaciones sin fines de lucro a las que se les conceden exenciones fiscales para servir a sus comunidades— que venden la deuda en acuerdos privados a empresas de cobros que, a su vez, persiguen a los pacientes.

"Se acosa a las personas a toda hora. Muchos acuden a nosotros sin saber de dónde procede la deuda", explicó Eric Zell, abogado supervisor de la Sociedad de Ayuda Legal de Cleveland. "Parece una epidemia".

En deuda con los hospitales, las tarjetas de crédito y los familiares

La crisis de la deuda en Estados Unidos se debe a una simple realidad: la mitad de los adultos estadounidenses no tiene dinero para cubrir una factura médica inesperada de $500, según la encuesta de KFF.

Como resultado, muchos simplemente no pagan. La avalancha de facturas impagas ha convertido la deuda médica en la forma más común de deuda en los registros de crédito de los consumidores.

El año pasado, el 58% de las deudas en los registros de cobros eran por una factura médica, según la Oficina de Protección Financiera del Consumidor (CFPB). Eso es casi cuatro veces más que las deudas atribuibles a facturas de telecomunicaciones, la siguiente forma de deuda más común en los registros de crédito.

Pero, en la investigación de KHN-NPR, se muestra que la deuda médica en los informes de crédito representa solo una fracción del dinero que los estadounidenses deben por atención de salud.

Es difícil saber cuántas deudas médicas tienen los estadounidenses en total, porque muchas no se registran. Pero un análisis anterior de KFF de los datos federales estimó que la deuda médica colectiva totalizó al menos $195 mil millones en 2019, más grande que la economía de Grecia.

Los saldos de las tarjetas de crédito, que tampoco se contabilizan como deuda médica, pueden ser sustanciales, según un análisis de los registros de tarjetas de crédito realizado por el Instituto JPMorgan Chase. El grupo de investigación financiera halló que el saldo mensual del titular típico de una tarjeta se disparaba un 34% después de un gasto médico importante.

Después, los saldos mensuales se reducen a medida que se pagan las facturas. Sin embargo, durante un año, se mantuvieron un 10% por encima de su nivel anterior al gasto médico. Los saldos de un grupo comparable de titulares de tarjetas sin un gasto médico importante se mantuvieron relativamente estables.

No está claro qué parte de los saldos más elevados se convirtió en deuda, ya que los datos del instituto no distinguen entre los titulares de tarjetas que pagan su saldo cada mes y los que no. Pero alrededor de la mitad de los titulares de tarjetas de todo el país tiene un saldo en sus tarjetas, lo que suele añadir intereses y comisiones.

Deudas grandes y pequeñas

Para muchos estadounidenses, las deudas por atención médica o dental pueden ser relativamente bajas. Aproximadamente un tercio debe menos de $1,000, según la encuesta de KFF.

Pero incluso las deudas más pequeñas pueden pasar factura.

Los cobradores persiguieron por años a Edy Adams, una estudiante de medicina de 31 años, de Texas, por un examen médico al que se sometió después de haber sido agredida sexualmente.

Adams se había graduado recientemente de la universidad y vivía en Chicago.

La policía nunca encontró al agresor. Pero dos años después de la agresión, Adams empezó a recibir llamadas de cobradores diciendo que debía $130,58.

La ley de Illinois prohíbe facturar a las víctimas por este tipo de pruebas. Pero no importaba cuántas veces Adams explicara el error, las llamadas seguían, y cada una la obligaba, según ella, a revivir el peor día de su vida.

A veces, cuando los cobradores llamaban, Adams rompía a llorar por teléfono. "Estaba desesperada", recordó. "Me perseguía esa factura zombi. No podía pararla".

Las deudas de salud también pueden ser catastróficas.

Sherrie Foy, de 63 años, y su marido, Michael, vieron cómo su jubilación, cuidadosamente planificada, se truncó cuando hubo que extirpar el colon de Foy.

Después de que Michael se jubilara de Consolidated Edison en Nueva York, la pareja se trasladó a la zona rural del suroeste de Virginia. Sherrie disponía allí de espacio para cuidar de sus caballos rescatados.

La pareja había ahorrado y contaban con un seguro médico para retirados a través de Con Edison. Pero la intervención quirúrgica de Sherrie provocó numerosas complicaciones, meses de hospitalización y facturas médicas que superaron el límite de un millón de dólares del plan de salud de la pareja.

Cuando Foy no pudo pagar los más de $775,000 que debía al Sistema de Salud de la Universidad de Virginia, el centro médico la demandó, una práctica que en su día era habitual y que la universidad dijo haber frenado. La pareja se declaró en quiebra.

Los Foys cobraron una póliza de seguro de vida para pagar a un abogado especializado en quiebras y liquidaron las cuentas de ahorro que la pareja había creado para sus nietos.

"Nos quitaron todo lo que teníamos", contó Foy. "Ahora no tenemos nada".

Alrededor de 1 de cada 8 estadounidenses endeudados por facturas médicas debe $10,000 o más, según la encuesta de KFF.

Aunque la mayoría espera pagar su deuda, el 23% dijo que tardará al menos tres años; el 18% dijo que no espera pagarla nunca.

El amplio alcance de la deuda médica

La deuda lleva mucho tiempo acechando en las sombras de la atención de salud estadounidense.

En el siglo XIX, los pacientes masculinos del Hospital Bellevue de Nueva York tenían que transportar pasajeros por el East River y las madres primerizas tenían que fregar suelos para pagar sus deudas, según una historia de los hospitales de Estados Unidos escrita por Charles Rosenberg.

Sin embargo, los acuerdos eran en su mayoría informales. En la mayoría de los casos, los médicos se limitaban a perdonar las facturas que los pacientes no podían pagar, según el historiador Jonathan Engel. "No existía el concepto de estar en deuda médica".

En la actualidad, las deudas por facturas médicas y dentales afectan a casi todos los rincones de la sociedad estadounidense, y suponen una carga incluso para quienes tienen cobertura de seguro a través del trabajo o de programas gubernamentales como Medicare.

Casi la mitad de los estadounidenses de hogares que ganan más de $90,000 al año han contraído deudas de atención médica en los últimos cinco años, según la encuesta de KFF.

Las mujeres son más propensas que los hombres a tener deudas. Y los que son padres tienen más deudas de salud que las personas sin hijos.

Pero la crisis se ha ensañado con los más vulnerables y con los que no tienen seguro.

La deuda está más extendida en el sur, según un análisis de los registros de crédito realizado por el Urban Institute. Las protecciones de los seguros son más débiles, muchos de los estados no han ampliado Medicaid y las enfermedades crónicas están más extendidas.

En todo el país, según la encuesta, los adultos negros no hispanos tienen un 50% más de probabilidades de deber dinero por atención médica, y los adultos hispanos un 35% más de probabilidades que los blancos no hispanos. (Los hispanos pueden ser de cualquier raza o combinación de razas).

En algunos lugares, como la capital del país, las disparidades son aún mayores, según los datos del Urban Institute: la deuda médica en los vecindarios predominantemente minoritarios de Washington D.C. es casi cuatro veces más común que en los barrios blancos no hispanos.

En las comunidades de minorías que ya enfrentan menos oportunidades educativas y económicas, la deuda puede ser agobiante, señaló Joseph Leitmann-Santa Cruz, director ejecutivo de Capital Area Asset Builders, una organización sin fines de lucro que ofrece asesoramiento financiero a los residentes con bajos ingresos de Washington. "Es como tener otro brazo atado a la espalda", añadió.

Las deudas médicas también pueden impedir a los jóvenes ahorrar, terminar sus estudios o conseguir un empleo. Un análisis de los datos crediticios reveló que la deuda por atención médica alcanza su punto máximo para un estadounidense promedio a finales de los 20 años y principios de los 30, y luego disminuye a medida que envejecen.

La deuda médica de Cheyenne Dantona hizo descarrilar su carrera antes de que empezara.

A Dantona, de 31 años, le diagnosticaron un cáncer de la sangre cuando estaba en la universidad. El cáncer remitió, pero cuando Dantona cambió de plan de salud, tuvo que pagar miles de dólares en facturas médicas porque uno de sus proveedores principales estaba fuera de la red.

Se inscribió en una tarjeta de crédito médica, pero tuvo que pagar aún más intereses. Otras facturas fueron a parar a agencias de cobro, lo que dañó su puntaje de crédito. Dantona sigue soñando con trabajar con animales salvajes heridos y huérfanos, pero se ha visto obligada a volver a vivir con su madre en las afueras de Minneapolis.

"Ha quedado atrapada", dijo Desiree, la hermana de Dantona. "Su vida se ha detenido".

Barreras para la atención

Desiree Dantona dijo que la deuda también ha hecho que su hermana dude a la hora de buscar atención para asegurar que su cáncer siga en remisión.

Los proveedores de servicios médicos dicen que éste es uno de los efectos más perniciosos de la crisis de la deuda en Estados Unidos, ya que aleja a los enfermos de la atención médica y acumula estrés tóxico en los pacientes cuando son más vulnerables.

La tensión financiera puede ralentizar la recuperación de los pacientes e incluso aumentar sus probabilidades de muerte, según los investigadores del cáncer.

Sin embargo, el vínculo entre enfermedad y deuda es un rasgo definitorio de la atención sanitaria estadounidense, según el Urban Institute, que analizó los registros de crédito y otros datos demográficos sobre pobreza, raza y estado de salud.

Los condados de Estados Unidos con la mayor proporción de residentes con múltiples enfermedades crónicas, como diabetes y enfermedades cardíacas, también tienden a tener la mayor deuda médica. Esto hace que la enfermedad sea un factor de predicción de deuda médica más poderoso que la pobreza o el seguro.

En los 100 condados de Estados Unidos con los niveles más altos de enfermedades crónicas, casi una cuarta parte de los adultos tienen deudas médicas en sus registros de crédito, en comparación con menos de 1 de cada 10 en los condados más saludables.

El problema es tan generalizado que incluso muchos médicos y líderes empresariales admiten que la deuda se ha convertido en una lacra para el sistema de salud estadounidense.

"No hay ninguna razón en este país para que una deuda médica destruya a las personas", indicó George Halvorson, ex director general de Kaiser Permanente (KP), el mayor sistema médico integrado y plan de salud del país. KP tiene una política de ayuda financiera relativamente generosa, pero a veces demanda a los pacientes. (El sistema de salud no está afiliado a KHN).

Halvorson citó el crecimiento de los seguros de salud con deducibles elevados como un factor clave de la crisis de la deuda. "Los pacientes se arruinan al recibir atención médica", añadió, "aunque tengan seguro".

El papel de Washington

ACA reforzó las protecciones financieras para millones de estadounidenses, no solo aumentando la cobertura sanitaria, sino también estableciendo normas que se suponía debían limitar cuánto pagarían los pacientes de su propio bolsillo.

En alguna medida, la ley ha funcionado, según estudios. En California, se produjo un descenso del 11% en el uso mensual de préstamos basados en el salario después de que el estado ampliara la cobertura a través de ACA.

Pero los límites de la ley en cuanto a los gastos de bolsillo han resultado ser demasiado elevados para la mayoría de los estadounidenses. La normativa federal permite que los gastos máximos de los planes individuales sean de hasta $8,700.

Además, ACA no detuvo el crecimiento de los planes con deducibles elevados, que se han convertido en la norma en la última década. Esto ha obligado a un número cada vez mayor de estadounidenses a pagar miles de dólares de su propio bolsillo antes de que su cobertura entre en vigencia.

El año pasado, el deducible anual de un trabajador soltero con cobertura a través de su empleo superó los $1,400, casi cuatro veces más que en 2006, según una encuesta anual de empleadores realizada por KFF. El deducible para una familia puede llegar a los $10,000.

Mientras los planes de salud exigen a los pacientes que paguen más, los hospitales, las farmacéuticas y otros proveedores médicos están subiendo los precios.

De 2012 a 2016, los precios de la atención médica aumentaron un 16%, casi cuatro veces la tasa de inflación general, según un informe del Health Care Cost Institute, una organización sin fines de lucro.

Para muchos estadounidenses, la combinación de precios elevados y altos costos de bolsillo significa casi inevitablemente una deuda. La encuesta de KFF reveló que 6 de cada 10 adultos en edad de trabajar, con cobertura, se han endeudado para recibir atención médica en los últimos cinco años, una tasa solo ligeramente inferior a la de los no asegurados.

Incluso la cobertura de Medicare puede dejar a los pacientes pagos de miles de dólares por medicamentos y tratamientos, según estudios.

Aproximadamente un tercio de las personas mayores ha debido dinero por cuidados médicos, según la encuesta. Y el 37% dijo que ellos o alguien de su hogar se ha visto obligado a recortar gastos en comida, ropa y otros artículos de primera necesidad debido a la deuda; el 12% afirmó haber tomado un trabajo extra.

El creciente costo de la deuda ha suscitado un nuevo interés por parte de los políticos, los reguladores y los líderes del sector.

En marzo, tras las advertencias de la Oficina de Protección Financiera del Consumidor (CFPB), las principales empresas de información crediticia comunicaron que eliminarían de los informes de crédito de los consumidores las deudas médicas inferiores a $500, y las que se hubieran pagado.

En abril, la administración Biden anunció una nueva campaña de la CFPB contra los cobradores de deudas y una iniciativa del Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos para recopilar más información sobre la forma en que los hospitales proporcionan ayuda financiera.

Estas medidas fueron aplaudidas por los defensores de los pacientes. Sin embargo, es probable que los cambios no aborden las causas fundamentales de esta crisis nacional.

"La razón número 1, y las razones número 2, 3 y 4, por las que las personas se endeudan por motivos médicos es que no tienen dinero", aseguró Alan Cohen, cofundador de la aseguradora Centivo, quien ha trabajado en el ámbito de las prestaciones de salud durante más de 30 años. "No es complicado".

Buck, el padre de Arizona al que se le negó la atención, lo ha visto de primera mano al vender planes de Medicare a personas mayores. "He tenido personas mayores llorando al teléfono conmigo", dijo. "Es horroroso".

Ahora, con 30 años, Buck se enfrenta a sus propias luchas. Se recuperó de la infección intestinal, pero después de verse obligado a ir a la emergencia de un hospital, recibió miles de dólares en facturas médicas.

Y se acumularon más cuando la esposa de Buck tuvo que acudir a urgencias por quistes en los ovarios.

Hoy, los Buck, que tienen tres hijos, calculan que deben más de $50,000, incluidas las facturas médicas que cargaron a las tarjetas de crédito y que no pueden pagar.

"Hemos tenido que recortar en todo", contó Buck. Sus hijos visten ropa usada. Escatiman en material escolar y dependen de la familia para los regalos de Navidad. Cenar fuera es un lujo.

"Me duele cuando mis hijos me piden ir a algún lugar y no puedo complacerlos", se lamentó Buck. "Me siento como si hubiera fallado como padre".

La pareja se prepara para declararse en bancarrota.

ACERCA DE ESTE PROYECTO

"Diagnóstico: Deuda" (Diagnosis: Debt) es una colaboración periodística entre KHN y NPR que explora la magnitud, el impacto y las causas de la deuda médica en Estados Unidos.

La serie se basa en un sondeo nacional llevado a cabo por KFF para la investigación que encuestó a una muestra representativa de 2,375 adultos estadounidenses, entre los que se encontraban 1,674 con deudas actuales o pasadas por facturas médicas o dentales.

El Urban Institute hizo una investigación adicional, en la que se analizaron datos de la oficina de crédito y otros datos demográficos sobre la pobreza, la raza y el estado de salud para explorar dónde se concentra la deuda médica en Estados Unidos y qué factores se asocian con los altos niveles de deuda.

El Instituto JPMorgan Chase analizó los registros de una muestra de titulares de tarjetas de crédito de Chase para ver cómo los saldos de los clientes pueden verse afectados por gastos médicos importantes.

Los reporteros de KHN y NPR también realizaron cientos de entrevistas con pacientes de todo el país; hablaron con médicos, líderes de la industria de la salud, defensores del consumidor, abogados especializados en deudas e investigadores; y revisaron decenas de estudios y encuestas sobre la deuda médica.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry – Kaiser Health News