MODESTO, California – Britta Foster y Minerva Tiznado están en ligas diferentes en lo que respecta a la atención sanitaria.

Foster, que se casó con un miembro de la familia propietaria de la empresa avícola Foster Farms, con ingresos anuales de $2,500 millones, tiene cobertura de Blue Shield, así como un plan de atención primaria de alto nivel que le da acceso digital a su médico las 24/7, por una cuota anual de $5,900 que también cubre a su marido y a dos de sus hijos.

Tiznado es de Nayarit, México, y no tiene seguro. Tiene visitas gratuitas de atención primaria y grandes descuentos en medicamentos, pruebas de laboratorio y diagnóstico por imagen.

Pero Tiznado, de 32 años, y Foster, de 48, reciben atención médica en el mismo lugar: Luke’s Family Practice, en esta ciudad del Valle Central de unos 217,000 habitantes. Luke’s, una clínica con una plantilla de cuatro personas situada en un anodino centro comercial, ofrece una combinación poco ortodoxa de medicina a medida para los más adinerados, y atención benéfica para los que no tienen seguro.

Las cuotas anuales que St. Luke’s cobra a la familia de Foster y a otros 550 pacientes que pagan ayudan a cubrir la atención gratuita de un número algo mayor de pacientes sin seguro, muchos de ellos, como Tiznado, inmigrantes de habla hispana que no pueden obtener Medicaid por no tener documentos.

La clínica no acepta ningún tipo de seguro, pero exige a los pacientes que pagan que tengan cobertura para afrontar los gastos médicos fuera de su ámbito de atención.

Estos pacientes, a los que St. Luke’s llama “benefactores”, dicen estar contentos de participar en este modelo “Robin Hood”. Les proporciona una atención muy personalizada con gran acceso a sus médicos y la satisfacción emocional de apoyar a los menos privilegiados, los “beneficiarios”.

Foster dijo que para su familia ha sido un “enorme beneficio” poder enviar un mensaje de texto o llamar a su médico en cualquier momento y ser atendidos en poco tiempo: “Saber que su grupo está aquí también para servir a nuestra comunidad hace que todo parezca aún más importante”.

Tiznado, que fue a la clínica una mañana de septiembre para una revisión programada de quistes ováricos, dijo que St Luke’s “nos ha ayudado mucho, económicamente y en todos los sentidos. Creo que, si nos mudáramos a otro lugar, seguiría viniendo aquí”.

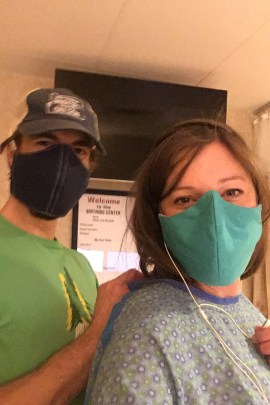

Pero Tiznado y los demás pacientes sin seguro no tienen el mismo acceso 24/7 que los benefactores. Los dos grupos utilizaban salas de espera separadas hasta que llegó la pandemia.

Luke’s es una respuesta local a los problemas sistémicos de la sanidad estadounidense, como el agotamiento de los médicos, la insatisfacción de los pacientes y el hecho de que millones de personas sigan careciendo de asistencia.

Casi 3,2 millones de californianos, entre ellos 1,3 millones de indocumentados, no tendrán seguro en 2022, aunque el estado está ampliando gradualmente la cobertura de Medicaid a muchos inmigrantes. Luke’s forma parte del movimiento a favor de la atención primaria directa, una alternativa para los doctores que huyen de los grupos médicos dominados por los seguros.

Cada año se abren en Estados Unidos unos 200 consultorios de atención primaria directa, y en la actualidad hay 1,581 que emplean a unos 3,000 médicos, según el doctor Philip Eskew, fundador de DPC Frontier, que ofrece recursos a médicos que quieren hacer el cambio. Se trata de una pequeña porción de los casi 209,000 médicos de atención primaria que hay en los Estados Unidos.

“Es cierto que somos un movimiento pequeño en este momento”, señaló Eskew.

Sus mayores retos son de tipo normativo. Por ejemplo, si las clínicas aceptan honorarios de personas inscritas en Medicare, sus médicos deben renunciar al reembolso de Medicare allí donde ejerzan. Además, algunos organismos reguladores estatales pueden considerar las prácticas de atención primaria directa como planes de salud e imponer condiciones o restricciones que dificulten o impidan su funcionamiento.

Los médicos de atención primaria directa suelen cobrar a los pacientes una cuota mensual o anual a cambio de un mayor acceso por teléfono, texto o video, tiempos de espera más cortos y visitas presenciales más largas. Y generalmente no aceptan seguros, lo que elimina la necesidad de perseguir facturas y autorizaciones de tratamiento.

“En mi antigua consulta, dedicábamos casi la mitad de nuestro tiempo procesando cobros. Pensé que, si podíamos deshacernos de todos esos gastos, podríamos dedicar más tiempo a los pacientes, y resultó ser cierto”, afirmó el doctor Bob Forester, creador del concepto y cofundador de St. Luke’s.

Muchos médicos de atención primaria directa no ven con buenos ojos a las empresas de alta tecnología propiedad de inversores, como One Medical o Forward Health. Se las considera empresas de atención primaria directa, pero sus críticos dicen que están más centradas en ampliar el volumen que en ofrecer un servicio personalizado.

“La atención primaria directa es aquella en la que el médico tiene una relación con el paciente. No tenemos que rendir cuentas a un inversor, porque nuestros inversores son nuestros pacientes”, explicó la doctora Maryal Concepción, médica de familia en Arnold, un pequeño pueblo en las montañas de California, y quien hace poco dejó una consulta comercial para poner en marcha su propia consulta de atención primaria directa.

Los pacientes de pago de St. Luke’s deben tener un seguro que cubra la hospitalización, las cirugías, la atención especializada, el diagnóstico por imágenes y los medicamentos recetados.

La clínica suele conseguir grandes descuentos para sus pacientes no asegurados. Por ejemplo, Quest Diagnostics les cobra sólo entre el 10% y el 15% de su precio habitual por los análisis de laboratorio, contó el doctor R.J. Heck, uno de los dos médicos de familia de St. Luke’s y cofundador de la clínica. Se suele remitir a los pacientes sin seguro que necesitan operaciones a Cirugía sin Fronteras, un centro quirúrgico de Bakersfield con tarifas reducidas.

St. Luke’s ha recibido recientemente una subvención de $75,000 para diagnóstico por imágenes, pruebas de laboratorio, radiografías y algunos medicamentos de la Legacy Health Endowment, una fundación local. Y trabaja con varios grupos de radiología que ofrecen descuentos, agregó Heck.

Tiznado, que necesita ecografías periódicas para sus quistes ováricos, explicó que paga unos $150 por ellas. “Si lo hiciera en otro lugar, me costaría entre $900 y $1,200”, dijo.

El estatus de entidad sin fines de lucro exenta de impuestos de St. Luke’s fomenta las donaciones, incluidas las de empresas benefactoras locales como Foster Farms y el productor de vinos E. & J. Gallo. Algunos trabajadores de las empresas que donan se encuentran entre los pacientes no asegurados de St. Luke’s.

La exención de impuestos también confiere un beneficio a los pacientes que pagan: pueden deducir de sus impuestos la parte de sus cuotas anuales que no utilizan para la atención médica. St. Luke’s les envía todos los años un extracto en el que se asigna un valor en dólares, basado en los precios de Medicare, de los servicios que han recibido.

Forester aseguró que St. Luke’s surgió de su preocupación por los no asegurados y su desprecio por los sistemas burocráticos. Pero “lo esencial”, dijo, “es que la idea de St. Luke’s nació en un momento inspirado de oración”. Forester y Heck lo pusieron en marcha hace más de 17 años como consultorio médico de inspiración católica.

Sin embargo, aunque los símbolos católicos adornan las paredes de St. Luke’s, muchos de sus pacientes no son cristianos, y la doctrina médica católica no es fundamental en su práctica.

“Aquí no viene nadie a controlar ni a decirnos lo que debemos o no debemos hacer”, afirmó la doctora Erin Kiesel, la otra médica de familia de la clínica.

Kiesel dijo que no prescribiría un aborto, pero que le diría a alguien a dónde ir si se lo pidiera, cosa que nadie ha hecho.

Heck y Kiesel aceptaron grandes recortes salariales para venir a St. Luke’s. Kiesel gana unos $60,000 menos al año que en su anterior consulta. Para ella, tener más tiempo con los pacientes, menos papeleo y un mejor equilibrio entre el trabajo y la vida personal compensa con creces el salario más bajo.

Los pacientes citaron las relaciones personales que han establecido con sus proveedores de St. Luke’s.

Paul Neumann, paciente de Heck desde hace 25 años y que lo siguió a St. Luke’s, dijo que esa relación ha sido un regalo del cielo.

Contó que en 2009 regresó de un viaje a Roma con neumonía. Cuando su mujer llamó a Heck a la mañana siguiente, éste acudió inmediatamente a la casa.

Neumann, de 84 años, paga a St. Luke’s más de $10,000 al año para él, su mujer y la familia de su hijo.

“Estaría encantado de extender un cheque por el doble”, añadió.

Este artículo fue producido por KHN, que publica California Healthline, un servicio editorialmente independiente de la California Health Care Foundation.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry – Kaiser Health News