As Walter Veal cared for residents at the Ludeman Developmental Center in suburban Chicago, he saw the potential future of his grandson, who has autism.

This story also ran on The Guardian. It can be republished for free.

So he took it on himself not just to bathe and feed the residents, which was part of the job, but also to cut their hair, run to the store to buy their favorite body wash and barbecue for them on holidays.

“They were his second family,” said his wife, Carlene Veal.

Even after COVID-19 struck in mid-March and cases began spreading through the government-run facility, which serves nearly 350 adults with developmental disabilities, Walter was determined to go to work, Carlene said.

Staff members were struggling to acquire masks and other personal protective equipment at the time, many asking family members for donations and wearing rain ponchos sent by professional baseball teams.

All Walter had was a pair of gloves, Carlene said.

By mid-May, rumors of some sick residents and staffers had turned into 274 confirmed positive COVID tests, according to the Illinois Department of Human Services COVID tracking site. On May 16, Walter, 53, died of the virus. Three of his colleagues had already passed, according to interviews with Ludeman workers, the deceased employees’ families and union officials.

State and federal laws say facilities like Ludeman are required to alert Occupational Safety and Health Administration officials about work-related employee deaths within eight hours. But facility officials did not deem the first staff death on April 13 work-related, so they did not report it. They made the same decision about the second and third deaths. And Walter’s.

It’s a pattern that’s emerged across the nation, according to a KHN review of hundreds of worker deaths detailed by family members, colleagues and local, state and federal records.

Workplace safety regulators have taken a lenient stance toward employers during the pandemic, giving them broad discretion to decide internally whether to report worker deaths. As a result, scores of deaths were not reported to occupational safety officials from the earliest days of the pandemic through late October.

KHN examined more than 240 deaths of health care workers profiled for the Lost on the Frontline project and found that employers did not report more than one-third of them to a state or federal OSHA office, many based on internal decisions that the deaths were not work-related — conclusions that were not independently reviewed.

Work-safety advocates say OSHA investigations into staff deaths can help officials pinpoint problems before they endanger other employees as well as patients or residents. Yet, throughout the pandemic, health care staff deaths have steadily climbed. Thorough reviews could have also prompted the Department of Labor, which oversees OSHA, to urge the White House to address chronic protective gear shortages or sharpen guidance to help keep workers safe.

Since no public agency releases the names of health care workers who die of COVID-19, a team of reporters building the Lost on the Frontline database has scoured local news stories, GoFundMe campaigns, and obituary and social media sites to identify nearly 1,400 possible cases. More than 260 fatalities have been vetted with families, employers and public records.

For this investigation, journalists examined worker deaths at more than 100 health care facilities where OSHA records showed no fatality investigation was underway.

At Ludeman, the circumstances surrounding the April 13 worker death might have shed light on the hazards facing Veal. But no state work safety officials showed up to inspect — because the Department of Human Services, which operates Ludeman and employs the staff, said it did not report any of the four deaths there to Illinois OSHA.

The department said “it could not determine the employees contracted COVID-19 at the workplace” — despite its being the site of one of the largest U.S. outbreaks. Since Veal’s death in May, dozens more workers have tested positive for COVID-19, according to DHS’ COVID tracking site.

OSHA inspectors monitor local news media and sometimes will open investigations even without an employer’s fatality report. Through Nov. 5, federal OSHA offices issued 63 citations to facilities for failing to report a death. And when inspectors do show up, they often force improvements — requiring more protective equipment for workers and better training on how to use it, files reviewed by KHN show.

Still, many deaths receive little or no scrutiny from work-safety authorities. In California, public health officials have documented about 200 health care worker deaths. Yet the state’s OSHA office received only 75 fatality reports at health care facilities through Oct. 26, Cal/OSHA records show.

Nursing homes, which are under strict Medicare requirements, reported more than 1,000 staff deaths through mid-October, but only about 350 deaths of long-term care facility workers appear to have been reported to OSHA, agency records show.

Workers whose deaths went unreported include some who took painstaking precautions to avoid getting sick and passing the virus to family members: One California lab technician stayed in a hotel during the workweek. An Arizona nursing home worker wore a mask for family movie nights. A Nevada nurse told his brother he didn’t have adequate PPE. Nevada OSHA confirmed to KHN that his death was not reported to the agency and that officials would investigate.

KHN asked health care employers why they chose not to report fatalities. Some cited the lack of proof that a worker was exposed on-site, even in workplaces that reported a COVID outbreak. Others cited privacy concerns and gave no explanation. Still others ignored requests for comment or simply said they had followed government policies.

“It is so disrespectful of the agencies and the employers to shunt these cases aside and not do everything possible to investigate the exposures,” said Peg Seminario, a retired union health and safety director who co-authored a study on OSHA oversight with scholars from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

A Department of Labor spokesperson said in a statement that an employer must report a fatality within eight hours of knowing the employee died and after determining the cause of death was a work-related case of COVID-19.

The department said employers also are bound to report a COVID death if it comes within 30 days of a workplace incident — meaning exposure to COVID-19.

Yet pinpointing exposure to an invisible virus can be difficult, with high rates of pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic transmission and spread of the virus just as prevalent inside a hospital COVID unit as out.

Those challenges, plus May guidance from OSHA, gave employers latitude to decide behind closed doors whether to report a case. So it’s no surprise that cases are going unreported, said Eric Frumin, who has testified to Congress on worker safety and is health and safety director for Change to Win, a partnership of seven unions.

“Why would an employer report unless they feel for some reason they’re socially responsible?” Frumin said. “Nobody’s holding them to account.”

Downside of Discretion

OSHA’s guidance to employers offered pointers on how to decide whether a COVID death is work-related. It would be if a cluster of infections arose at one site where employees work closely together “and there is no alternative explanation.” If a worker had close contact with someone outside of work infected with the virus, it might not have been work-related, the guidance says.

Ultimately, the memo says, if an employer can’t determine that a worker “more likely than not” got sick on the job, “the employer does not need to record that.”

In mid-March, the union that represented Paul Odighizuwa, a food service worker at Oregon Health & Science University, raised concerns with university management about the virus possibly spreading through the Food and Nutrition Services Department.

Workers there — those taking meal orders, preparing food, picking up trays for patient rooms and washing dishes — were unable to keep their distance from one another, said Michael Stewart, vice president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 328, which represents about 7,000 workers at OHSU. Stewart said the union warned administrators they were endangering people’s lives.

Soon the virus tore through the department, Stewart said. At least 11 workers in food service got the virus, the union said. Odighizuwa, 61, a pillar of the local Nigerian community, died on May 12.

OHSU did not report the death to the state’s OSHA and defended the decision, saying it “was determined not to be work-related,” according to a statement from Tamara Hargens-Bradley, OHSU’s interim senior director of strategic communications.

She said the determination was made “[b]ased on the information gathered by OHSU’s Occupational Health team,” but she declined to provide details, citing privacy issues.

Stewart blasted OHSU’s response. When there’s an outbreak in a department, he said, it should be presumed that’s where a worker caught the virus.

“We have to do better going forward,” Stewart said. “We have to learn from this.” Without an investigation from an outside regulator like OSHA, he doubts that will happen.

Stacy Daugherty heard that Oasis Pavilion Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Casa Grande, Arizona, was taking strict precautions as COVID-19 surged in the facility and in Pinal County, almost halfway between Phoenix and Tucson.

Her father, a certified nursing assistant there, was also extra cautious: He believed that if he got the virus, “he wouldn’t make it,” Daugherty said.

Mark Daugherty, a father of five, confided in his youngest son when he fell ill in May that he believed he contracted the coronavirus at work, his daughter said in a message to KHN.

Early in June, the facility filed its first public report on COVID cases to Medicare authorities: Twenty-three residents and eight staff members had fallen ill. It was one of the largest outbreaks in the state. (Medicare requires nursing homes to report staff deaths each week in a process unrelated to OSHA.)

By then, Daugherty, 60, was fighting for his life, his absence felt by the residents who enjoyed his banjo, accordion and piano performances. But the country’s occupational safety watchdog wasn’t called in to figure out whether Daugherty, who died June 19, was exposed to the virus at work. His employer did not report his death to OSHA.

“We don’t know where Mark might have contracted COVID 19 from, since the virus was widespread throughout the community at that time. Therefore there was no need to report to OSHA or any other regulatory agencies,” Oasis Pavilion’s administrator, Kenneth Opara, wrote in an email to KHN.

Since then, 15 additional staffers have tested positive and the facility suspects a dozen more have had the virus, according to Medicare records.

Gaps in the Law

If Oasis Pavilion needed another reason not to report Daugherty’s death, it might have had one. OSHA requires notice of a death only within 30 days of a work-related incident. Daugherty, like many others, clung to life for weeks before he died.

That is one loophole — among others — in work-safety laws that experts say could use a second look in the time of COVID-19.

In addition, federal OSHA rules don’t apply to about 8 million public employees. Only government workers in states with their own state OSHA agency are covered. In other words, in about half the country if a government employee dies on the job — such as a nurse at a public hospital in Florida, or a paramedic at a fire department in Texas — there’s no requirement to report it and no one to look into it.

So there was little chance anyone from OSHA would investigate the deaths of two health workers early this year at Central State Hospital in Georgia — a state-run psychiatric facility in a state without its own worker-safety agency.

On March 24, a manager at the facility had warned staff they “must not wear articles of clothing, including Personal Protective Equipment” that violate the dress code, according to an email KHN obtained through a public records request.

Three days later, what had started as a low-grade illness for Mark DeLong, a licensed practical nurse at the facility, got serious. His cough was so severe late on March 27 that he called 911 — and handed the phone to his wife, Jan, because he could barely speak, she said.

She went to visit him in the hospital the next day, fully expecting a pleasant visit with her karaoke partner. “By the time I got there it was too late,” she said. DeLong, 53 “had passed.”

She learned after his death that he’d had COVID-19.

Back at the hospital, workers had been frustrated with the early directive that employees should not wear their own PPE.

Bruce Davis had asked his supervisors if he could wear his own mask but was told no because it wasn’t part of the approved uniform, according to his wife, Gwendolyn Davis. “He told me ‘They don’t care,’” she said.

Two days after DeLong’s death, the directive was walked back and employees and contractors were informed they could “continue and are authorized to wear Personal Protective Gear,” according to a March 30 email from administrators. But Davis, a Pentecostal pastor and nursing assistant supervisor, was already sick. Davis worked at the hospital for 27 years and saw little distinction between the love he preached at the altar and his service to the patients he bathed, fed and cared for, his wife said.

Sick with the virus, Davis died April 11.

At the time, 24 of Central State’s staffers had tested positive, according to the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, which runs the facility. To date, nearly 100 staffers and 33 patients at Central State have gotten the virus, according to figures from the state agency.

“I don’t think they knew what was going on either,” Jan DeLong said. “Somebody needs to check into it.”

In response to questions from KHN, a spokesperson for the department provided a prepared statement: “There was never a ban on commercially available personal protective equipment, even if the situation did not call for its use according to guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Georgia Department of Public Health at the time.”

KHN reviewed more than a dozen other health worker deaths at state or local government workplaces in states like Texas, Florida and Missouri that went unreported to OSHA for the same reason — the facilities were run by government agencies in a state without its own worker safety agency.

Inside Ludeman

In mid-March, staff members at the Ludeman Developmental Center were desperate for PPE. The facility was running low on everything from gloves and gowns to hand sanitizer, according to interviews with current and former workers, families of deceased workers, and union officials.

Due to a national shortage at the time, surgical masks went only to staffers working with known positive cases, said Anne Irving, regional director for AFSCME Council 31, the union that represents Ludeman employees.

Residents in the Village of Park Forest, Illinois, where the facility is located, tried to help by sewing masks or pivoting their businesses to produce face shields and hand sanitizer, said Mayor Jonathan Vanderbilt. But providing enough supplies for more than 900 Ludeman employees proved difficult.

Michelle Abernathy, 52, a newly appointed unit director, bought her own gloves at Costco. In late March, a resident on Abernathy’s unit showed symptoms, said Torrence Jones, her fiancé who also works at the facility. Then Abernathy developed a fever.

When she died on April 13 — the first known Ludeman staff member lost to the pandemic — the Illinois Department of Human Services, which runs Ludeman, made no report to safety regulators. After seeing media reports, Illinois OSHA sent the agency questions about Abernathy’s daily duties and working conditions. Based on DHS’ responses and subsequent phone calls, state OSHA officials determined Abernathy’s death was “not work-related.”

Barbara Abernathy, Michelle’s mom, doesn’t buy it. “Michelle was basically a hermit,” she said, going only from work to home. She couldn’t have gotten the virus anywhere else, she said. In response to OSHA’s inquiry for evidence that the exposure was not related to her workplace, her employer wrote “N/A,” according to documents reviewed by KHN.

Two weeks after Abernathy’s passing, two more employees died: Cephus Lee, 59, and Jose Veloz III, 52. Both worked in support services, boxing food and delivering it to the 40 buildings on campus. Their deaths were not reported to Illinois OSHA.

Veloz was meticulous at home, having groceries delivered and wiping down each item before bringing it inside, said his son, Joseph Ricketts.

But work was another story. Maintaining social distance in the food prep area was difficult, and there was little information on who had been infected or exposed to the virus, according to his son.

“No matter what my dad did, he was screwed,” Ricketts said. Adding, he thought Ludeman did not do what it should have done to protect his dad on the job.

A March 27 complaint to Illinois OSHA said it took a week for staff to be notified about multiple employees who tested positive, according to documents obtained by the Documenting COVID-19 project at the Brown Institute for Media Innovation and shared with KHN. An early April complaint was more frank: “Lives are endangered,” it said.

That’s how Rose Banks felt when managers insisted she go to work, even though she was sick and awaiting a test result, she said. Her husband, also a Ludeman employee, had already tested positive a week earlier.

Banks said she was angry about coming in sick, worried she might infect co-workers and residents. After spending a full day at the facility, she said, she came home to a phone call saying her test was positive. She’s currently on medical leave.

With some Ludeman staff assigned to different homes each shift, the virus quickly traveled across campus. By mid-May, 76 staff and 198 residents had tested positive, according to DHS’ COVID tracking site.

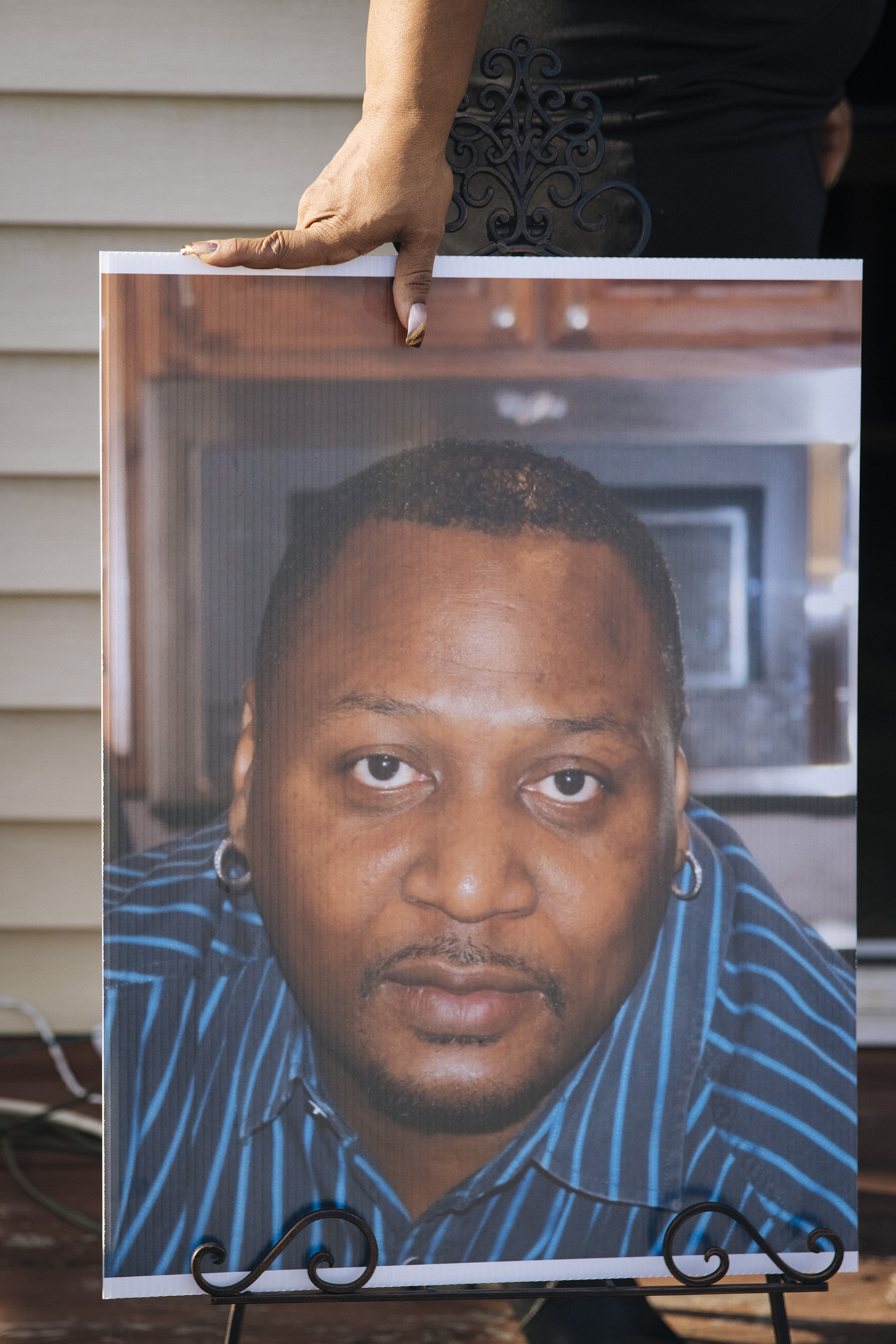

Carlene Veal said her husband, Walter, was tested at the facility in late April. But by the time he got the results weeks later, she said, he was already dying.

Carlene can still picture the last time she saw Walter, her high school sweetheart and a man she called her “superhero” for 35 years of marriage and raising four kids together. He was lying on a gurney in their driveway with an oxygen mask on his face, she said. He pulled the mask down to say “I love you” one last time before the ambulance pulled away.

The Illinois Department of Human Services said that, since the beginning of the pandemic, it has implemented many new protocols to mitigate the outbreak at Ludeman, working as quickly as possible based on what was known about the virus at the time. It has created an emergency staffing plan, identified negative-airflow spaces to isolate sick individuals and made “extensive efforts” to procure more PPE, and it is testing all staffers and residents regularly.

“We were deeply saddened to lose four colleagues who worked at Ludeman Developmental Center and succumbed to the virus,” the agency said in a statement. “We are committed to complying with and following all health and safety guidelines for COVID-19.”

The number of new cases at Ludeman has remained low for several months now, according to DHS’ COVID tracking site.

But that does little to console the families of those who have died.

When a Ludeman supervisor called Barbara Abernathy in June to express condolences and ask if there was anything they could do, Abernathy didn’t know how to respond.

“There was nothing they could do for me now,” she said. “They hadn’t done what they needed to do before.”

Shoshana Dubnow, Anna Sirianni, Melissa Bailey and Hannah Foote contributed to this report.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Health Industry – Kaiser Health News