Aspen was an early COVID-19 hot spot in Colorado, with a cluster of cases in March linked to tourists visiting for its world-famous skiing. Tests were in short supply, making it difficult to know how the virus was spreading.

So in April, when the Pitkin County Public Health Department announced it had obtained 1,000 COVID-19 antibody tests that it would offer residents at no charge, it seemed like an exciting opportunity to evaluate the efforts underway to stop the spread of the virus.

“This test will allow us to get the epidemiological data that we’ve been looking for,” Aspen Ambulance District director Gabe Muething said during an April 9 community meeting held online.

However, the plan soon fell apart amid questions about the reliability of the test from Aytu BioScience. Other ski towns such as Telluride, Colorado, and Jackson, Wyoming, as well as the less wealthy border community of Laredo, Texas, were also drawn to antibody testing to inform decisions about how to exit lockdown. But they, too, determined the tests weren’t living up to their promise.

The allure of antibody tests is understandable. Although they can’t find active cases of COVID-19, they can identify people who previously have been infected with the coronavirus that causes the disease, which could give health officials important epidemiological information about how widely it has spread in a community and the extent of asymptomatic cases. In theory, at least, antibodies would be present in such people whether they had a severe case, little more than a dry cough or no complaints at all.

Even more enticing: These tests were billed as a path to restart local economies by identifying people who might be immune to the virus and could therefore safely return to the public sphere.

But, in these and other communities, testing programs initially slated to test hundreds or thousands have been scaled back or put on hold.

“I don’t think these tests are ready for clinical use yet,” said University of California-San Francisco immunologist Dr. Alexander Marson, who has studied their reliability. He and his team vetted 12 different antibody tests and found all but one turned up false positives — implying that someone had antibodies when they didn’t ― with false-positive rates reaching as high as 16%. (The study is preliminary and has not been peer-reviewed yet.)

More than 100 antibody tests are currently available in the U.S., including offerings by commercial labs, academic centers and small entrepreneurial ventures. As serious questions emerged earlier this month about the accuracy of the tests and the usefulness of the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said it will require companies to submit validation data on their products and apply for emergency-use authorizations for their products. (Previously, companies were allowed to sell their tests without review from the FDA, as long as they did their own validation and included a disclaimer.) And the American Medical Association said on May 14 that the tests should not be used to assess an individual’s immunity or when to end physical distancing.

And this week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released new guidelines warning that antibody test results can have high false positive rates and should not be used to make decisions about returning people to work, schools, dorms or other places where people congregate.

Once hailed as a solution, the current crop of tests, which have not been thoroughly vetted by any regulatory agency, now seem more likely to add chaos and uncertainty to a situation already fraught with anxiety. “To give people a false sense of security has a lot of danger right now,” said Dr. Travis Riddell, the health officer for Teton County, which includes Jackson, Wyoming.

Accuracy Questions Raised

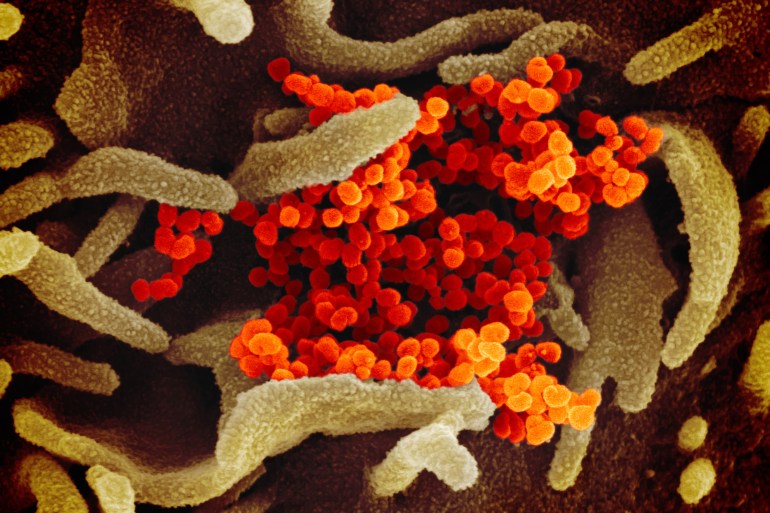

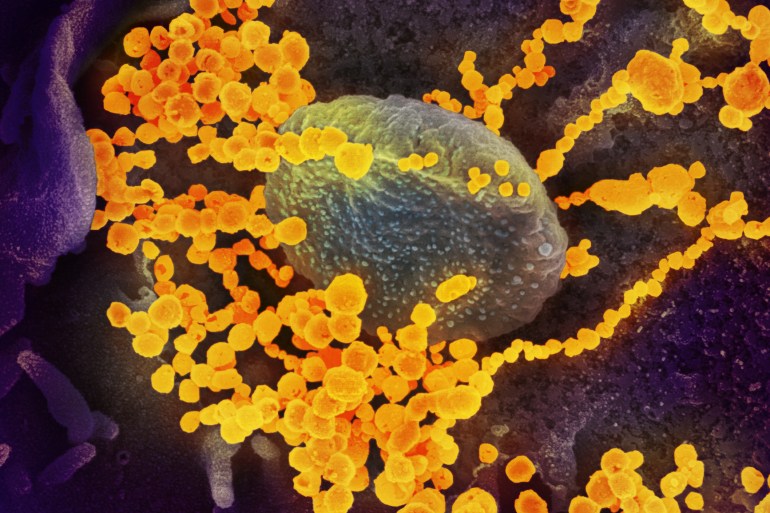

The gold standard for confirming an active COVID-19 infection is to take a swab from the nasopharynx and test it for the presence of viral RNA. The antibody tests instead parse the blood for antibodies against the COVID-19 virus. It takes time for an infected person to produce antibodies, so these tests can’t diagnose an ongoing infection, only indicate that a person has encountered the virus.

In Aspen, county officials knew the FDA had not approved the Aytu BioScience test, which the Colorado-based company was importing from China. So they first conducted their own validation tests, said Bill Linn, spokesperson for the Pitkin County Incident Management Team. “We weren’t reassured enough by our own testing to feel like we should move ahead.”

In Laredo, officials had been told by one of the community members helping to arrange the purchase of 20,000 tests from the Chinese company Anhui DeepBlue Medical Technology that they were FDA-approved, but the city’s own validation trials revealed only about a 20% accuracy rate, said Laredo spokesperson Rafael Benavides. Before Laredo could pay for the tests, Benavides said, an arm of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement seized them and launched an investigation.

Neither Anhui DeepBlue Medical Technology, nor Aytu returned requests for comment.

In March, Covaxx, a company led by two part-time Telluride residents, offered to test residents of the town and the surrounding county with an antibody test it had developed. But the project was suspended indefinitely when the company’s testing facility fell behind on processing them.

The county is committed to doing a second round of testing but is evaluating how to proceed, said San Miguel County spokesperson Susan Lilly. “The question is how do you target it to be the most relevant clinically and for the public health team’s decision-making moving forward?”

Officials Back Off, Community Members Step In

On May 4, the FDA updated its antibody test policy to require that manufacturers submit validation data, but it is still allowing the tests to be sold without the normal lengthy vetting and approval process, which includes demonstrating safety and effectiveness.

In some wealthy areas, government officials had been offering free tests from startups with local investors. In Jackson, for example, a venture capitalist with an investment in Covaxx, the test used in Telluride, offered to help the city obtain 1,000 tests. But after reviewing the offer, Teton County declined over concerns about the test’s accuracy. “If a person tests positive, what does that mean? And is that useful information? We just don’t know yet,” Riddell said.

Covaxx spokesperson John Schaefer said in a statement that the test had been validated on more than 900 blood samples and is being reviewed by the FDA.

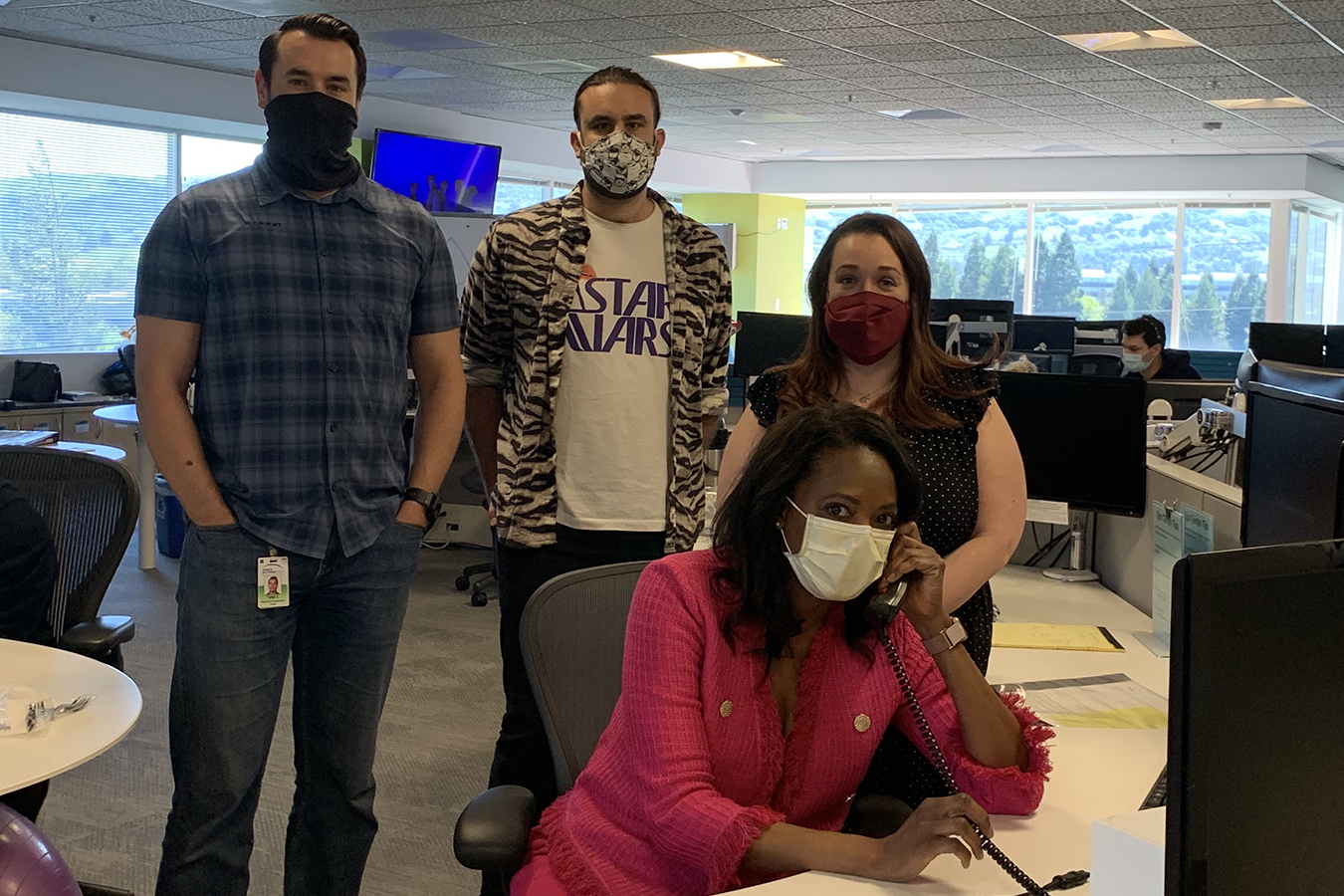

After Teton County officials decided against community antibody testing, a private nonprofit, Test Teton Now, sprung up to provide free COVID-19 antibody testing using the Covaxx test for roughly 8,000 people, about a third of the county’s residents. As of May 22, they’d raised $396,000 and tested 843 samples. The group has “done a lot” to verify the Covaxx tests, said Test Teton Now president Shaun Andrikopoulos. “I don’t want to call it validation, because we didn’t go through an independent review board, but we have sent our samples out to other labs.”

Organizers of Test Teton Now don’t share others’ concerns about the test’s utility. “We don’t encourage people to make any decisions about what they’re going to do or how they’re going to behave based on the results,” said the nonprofit’s spokesperson, Jennifer Ford.

What good is a test that can’t be used for practical purposes? “We think knowledge is power, and data is the beginning of knowledge,” Ford said. But unreliable data doesn’t give knowledge, it gives an illusion of knowledge.

So many unknowns remain, and false data may be worse than none. Even a very accurate test will produce a large number of false positives when used in a population where few people have been infected. If only 4% of people have actually been infected, a test with 95% accuracy would produce nine positive results for every 100 tests, five of which are false positives.

And that creates a danger that the tests could lead people to incorrectly think that they have antibodies that make them immune, which could have disastrous consequences if they changed their behavior as a result. Consider, for example, a person falsely told she had antibodies going to work at a nursing home, believing she couldn’t catch or spread the virus to anyone.

It’s not even known for sure that having antibodies makes someone immune. Researchers are hopeful that exposure can confer some level of immunity, but how strong that immunity might be and how long it might last remain unknown, said Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch.

So, having been burned once, Aspen has put antibody testing on hold and is instead focusing on identifying and isolating people who are sick or at risk of becoming so. “It’s actually a step back to where we started,” Linn said.

Given the remaining unknowns about immunity and COVID-19, the best methods for addressing the pandemic in communities may be the most time-tested ones, Linn said. “Put the sick people in places where they can’t get anyone else sick. It’s the bread and butter of epidemiology.”

from Health Industry – Kaiser Health News